|

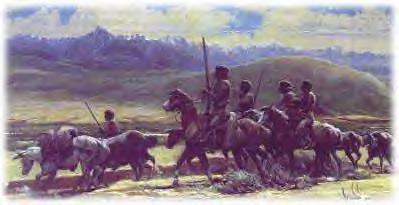

As the Corps of Discovery bicentennial approaches, Meriwether Lewis and William Clark

are being heralded as astronauts in buckskin who defined American character by exploring a continent.

But the Confederated Salish and Kootenai Tribes of the Flathead Nation in western Montana are opting out of the

celebration. They reflect a view of native peoples that is being heard across the Northern Plains, Rocky Mountains

and Pacific Northwest. To them, the Corps of Discovery was the vanguard of a conquest that wrought fundamental

change in a centuries-old way of life.

"What we have done is tried not to participate in the celebration except on an educational level," says

Tony Incashola, chairman of the Salish-Pend d'Oreille Culture Committee.

The group has produced a monograph pointing out that, in a 24-hour timeline of tribal history, "Columbus would

arrive at about 11 p.m., and Lewis and Clark would arrive around 11:37 p.m. ... The Salish and Pend d'Oreille were

here, a sovereign nation, a fully and richly developed culture."

Lynda Earring, director of graduate education at Oglala Lakota College, says the contact with Lewis and Clark and

subsequent domination by their culture have had eternal repercussions for Indians.

"I don't think people really, really realize what that meant, what it actually did," she says. "Every

day we native people deal with that reality from the time we get up until the time we go to bed, in all aspects

of our lives."

James Ronda, a historian at Tulsa University and author of "Lewis and Clark Among the Indians,"

describes the challenge the Corps of Discovery represented for the tribes whose land it passed through. James Ronda, a historian at Tulsa University and author of "Lewis and Clark Among the Indians,"

describes the challenge the Corps of Discovery represented for the tribes whose land it passed through.

"Here is an aggressive, expansionist neighbor who doesn't just want to trade. They want the land.

"(President Thomas) Jefferson thinks of the West as a Garden of Eden. That means farmers, and that means these

white guys will take the land away from the people already there," he says. "Lewis and Clark represent

this coming wave of empire. That is the most significant thing about them, and it puts a pretty hard edge on them."

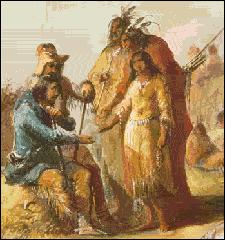

Dealing with tribes

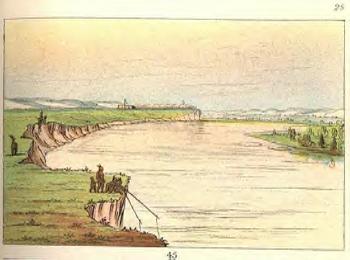

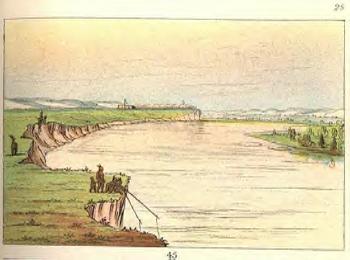

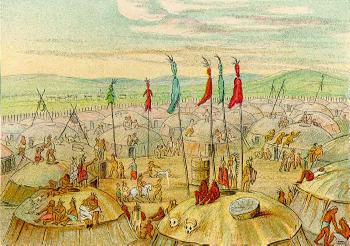

Each tribe had different experiences with Lewis and Clark. The Corps' mission changed as it moved west. In the

lands of the Louisiana Purchase between the Mississippi River and Rocky Mountains, the corps tried to estimate

the Indian population and determine where people lived; the explorers noted whether tribes were trading with British

fur traders in Canada or Americans in St. Louis.

Herb Hoover, a University of South Dakota historian, says they tried to identify tribal members amenable to diplomatic

relations, then set them up as chiefs by adorning them with medallions, hats, coats and U.S. flags.

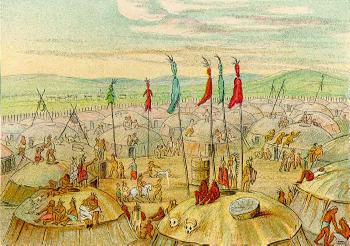

The first group greeted this way was the Yanktons, part of about 30,000 Dakota, Nakota and Lakota people living

on the Northern Plains.

"The Yanktons have had the longest formal relationship with the U.S. government," Hoover points out.

Lewis and Clark also informed the tribes within the Louisiana Purchase they were now dependent nations, under the

control of the United States.

Ronda says Lewis and Clark were carrying out Jefferson's vision. The explorers "were there

to announce to the tribes, 'You have a new Great Father,' " Ronda says. Ronda says Lewis and Clark were carrying out Jefferson's vision. The explorers "were there

to announce to the tribes, 'You have a new Great Father,' " Ronda says.

"Jefferson's notion in making treaties with native people is that they are junior partners in the American

Empire," he says. "Jefferson always assumes he is not dealing with equals."

Beyond the Louisiana Purchase, in the Northwest, Lewis and Clark made no treaties. Instead, they struck practical

alliances with the tribes for food, horses and information. Clark may have fathered a son with a Flathead woman

in Montana, and the pair made extravagant promises to arm the Shoshones and Nez Perce "that it was not in

their power to keep," Ronda says.

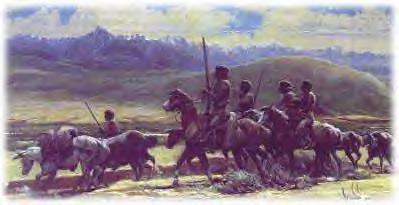

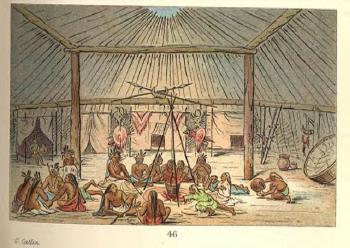

For tribes along the route, the Corps ranged from a tourist attraction to an unsettling, confusing new phenomenon.

Ronda imagines Indians lining the banks of the Missouri watching "a whole bunch of guys come up the river

in the biggest boat you've ever seen."

First impressions

Northern Plains tribes had dealt with white traders for about 20 years before the Corps of Discovery appeared,

says Mary Jane Schneider, a professor of Indian Studies at the University of North Dakota, so in that respect Lewis

and Clark were not strange.

"Indian people were not impressed with them," Schneider says of the Corps. "The only person they

thought was worthwhile was the gunsmith, because he fixed things."

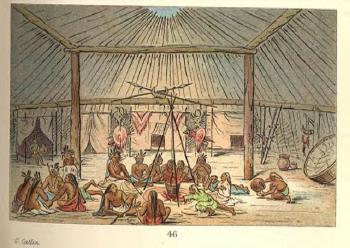

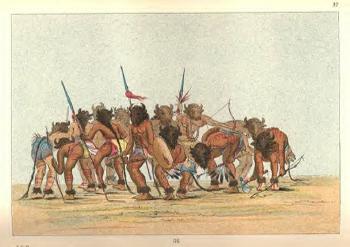

Much has been made of the fact that Lewis and Clark presented a corn grinder to the Mandan, Hidatsu and Arikara

tribes with whom they wintered in North Dakota. Those tribes already were practicing agriculture. But Schneider

dismisses any special significance. She points out the Indians "took apart the machine and turned it into

other metal tools they needed more than a corn grinder."

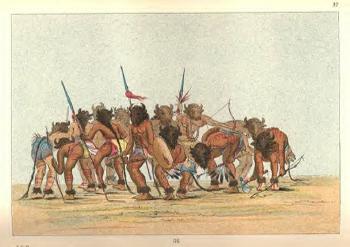

As the Corps moved west into the Rockies and beyond, it met tribes who had not seen white men.

The Salish-Pend d'Oreille Culture Committee monograph points out the confusion that reigned in these meetings. As the Corps moved west into the Rockies and beyond, it met tribes who had not seen white men.

The Salish-Pend d'Oreille Culture Committee monograph points out the confusion that reigned in these meetings.

"Many non-Indian historians and filmmakers have depicted the encounter between Indian people and the Lewis

and Clark expedition as a story of respectful cultural exchange and mutual understanding," it states.

In fact, the Salish thought York, Clark's African-American servant, might have painted himself black for war. They

thought the expedition members might have been in mourning because their hair was cut short. The Indians could

not determine if the expedition was a war party or pitiful wanderers.

"The non-Indian accounts, and especially the later histories of the expedition, downplay this misunderstanding

or even deny it," the monograph says. "The romantic glow of Lewis and Clark rests in part on the myth

that Indian people welcomed the expedition in the full knowledge of their intentions."

Sacajawea

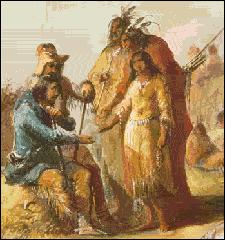

One enduring image that springs from the Corps of Discovery is Sacajawea, the wife of corps interpreter Toussaint

Charbonneau, who joined the expedition in North Dakota.

She was a Shoshone, born in eastern Idaho, but she was kidnapped at about age 10 by Hidatsu raiders

and brought back to North Dakota, where she was sold to Charbonneau at about age 16. She was a Shoshone, born in eastern Idaho, but she was kidnapped at about age 10 by Hidatsu raiders

and brought back to North Dakota, where she was sold to Charbonneau at about age 16.

Clark noted her knowledge of the mountains saved weeks of travel for the expedition, and she was a valuable translator

when the expedition moved into her native country.

Sacajawea has become a symbol of warm cooperation between the corps and native people. Biographer Harold Howard

notes she has more school buildings and monuments named for her than any other American woman.

Her later life is wrapped in mystery. One account has her dying in St. Louis at about age 25 of "a putrid

fever." Shoshone oral history has her living into her 90s and being buried at Fort Washakie in Wyoming. Clark

did raise her son, Jean Baptiste, whom she left in his care in St. Louis when she came there with Charbonneau.

Early impact

For all the contemporary interest in the expedition, historians suggest it had little immediate

impact. Lewis died in 1809. The war of 1812 closed the frontier for several years after Lewis and Clark returned,

and parts of their journals were first published, in an edition of only 2,000 copies, in 1814. Ronda says the most

important thing in that edition was Clark's map of the West, which served as a guide for expanding fur trade to

the Rockies. For all the contemporary interest in the expedition, historians suggest it had little immediate

impact. Lewis died in 1809. The war of 1812 closed the frontier for several years after Lewis and Clark returned,

and parts of their journals were first published, in an edition of only 2,000 copies, in 1814. Ronda says the most

important thing in that edition was Clark's map of the West, which served as a guide for expanding fur trade to

the Rockies.

Beyond that, "what is published is not the science or the ethnography, but a glorified adventure story,"

Ronda says. "It has less impact than we think."

From the perspective of the 21st century, the expedition also was a staggering missed opportunity to enlighten

the nation, especially Jefferson, about a way of life practiced by indigenous peoples on the frontier. Jefferson's

notion that the West must be subjugated held sway, with consequences that have persisted nearly 200 years.

While Clark, particularly, had some empathy for native American cultures, neither he nor Lewis could convey to

Jefferson the richness of those cultures. Nor did they try, Ronda says.

"That was a notion that was utterly foreign to Lewis and Clark," he says. "The very idea of cultures

being different but equal was beyond what they could think."

Cultural struggle

The upshot for Indians, after they were overwhelmed by war and the waves of settlement that followed Lewis and

Clark, was first an attempt to eradicate their cultures, and more recently, a need to accommodate those cultures

to the dominant, European-based way of life in the United States.

"We have been taught to think linearly, and our people didn't think that way," Earring, of Oglala Lakota

College, says. "We still don't. We look at the whole picture."

But nearly 200 years after Lewis and Clark heralded the profound changes coming to the West, Earring says places

such as Oglala Lakota College are coming to terms with the impact of those changes in ways favorable to Indians.

They are making European models of education and government adapt to native American ways of thinking.

"It has taken a number of years to figure this out," she says. "But we've got it going now. We're

good to go, and we will change the face of education."

Lewis and Clark

http://www.senate.gov/~dorgan/lewis_and_clark/index.html

Reprinted under the Fair Use http://www4.law.cornell.edu/uscode/17/107.html

doctrine of international copyright law.

<><<<<<>>>>><><<<<>

Tsonkwadiyonrat (We are ONE Spirit)

http://ishgooda.nativeweb.org/

<><<<<<>>>>><><<<<>

Native News:

http://ishgooda.nativeweb.org/natnews.htm

|

James Ronda, a historian at Tulsa University and author of "Lewis and Clark Among the Indians,"

describes the challenge the Corps of Discovery represented for the tribes whose land it passed through.

James Ronda, a historian at Tulsa University and author of "Lewis and Clark Among the Indians,"

describes the challenge the Corps of Discovery represented for the tribes whose land it passed through.  Ronda says Lewis and Clark were carrying out Jefferson's vision. The explorers "were there

to announce to the tribes, 'You have a new Great Father,' " Ronda says.

Ronda says Lewis and Clark were carrying out Jefferson's vision. The explorers "were there

to announce to the tribes, 'You have a new Great Father,' " Ronda says.  As the Corps moved west into the Rockies and beyond, it met tribes who had not seen white men.

The Salish-Pend d'Oreille Culture Committee monograph points out the confusion that reigned in these meetings.

As the Corps moved west into the Rockies and beyond, it met tribes who had not seen white men.

The Salish-Pend d'Oreille Culture Committee monograph points out the confusion that reigned in these meetings.

She was a Shoshone, born in eastern Idaho, but she was kidnapped at about age 10 by Hidatsu raiders

and brought back to North Dakota, where she was sold to Charbonneau at about age 16.

She was a Shoshone, born in eastern Idaho, but she was kidnapped at about age 10 by Hidatsu raiders

and brought back to North Dakota, where she was sold to Charbonneau at about age 16.  For all the contemporary interest in the expedition, historians suggest it had little immediate

impact. Lewis died in 1809. The war of 1812 closed the frontier for several years after Lewis and Clark returned,

and parts of their journals were first published, in an edition of only 2,000 copies, in 1814. Ronda says the most

important thing in that edition was Clark's map of the West, which served as a guide for expanding fur trade to

the Rockies.

For all the contemporary interest in the expedition, historians suggest it had little immediate

impact. Lewis died in 1809. The war of 1812 closed the frontier for several years after Lewis and Clark returned,

and parts of their journals were first published, in an edition of only 2,000 copies, in 1814. Ronda says the most

important thing in that edition was Clark's map of the West, which served as a guide for expanding fur trade to

the Rockies.