|

|

Canku Ota |

|

|

(Many Paths) |

||

|

An Online Newsletter Celebrating Native America |

||

|

July 14, 2001 - Issue 40 |

||

|

|

||

|

Teams Will Aid Natives in Schools |

||

|

by Rosemary Shinohara Anchorage Daily News-July 8, 2001 |

||

|

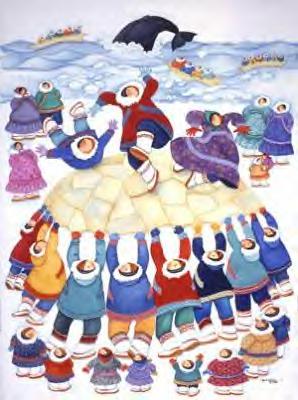

Up Up Away by Barbara Lavallee |

A nonprofit Native group plans to spend up to $2 million annually in Anchorage public schools to

help the many Native students who either give up and drop out or stay in school and earn low grades. A nonprofit Native group plans to spend up to $2 million annually in Anchorage public schools to

help the many Native students who either give up and drop out or stay in school and earn low grades. Beginning this fall, Cook Inlet Tribal Council Inc. proposes to send teams of three people, including a counselor, a tutor and a home coordinator, into middle schools and high schools to work one on one with Native students and their families. The project will start at a handful of schools and expand to more schools as more money becomes available. The Native nonprofit chose the plan it calls Partners for Success over another idea -- starting a charter school for Native teens -- because it can reach more students by working within existing schools, said Gloria O'Neill, president and chief executive officer of Cook Inlet Tribal Council. The Anchorage School District welcomes the help. "I'm very excited about working with them," superintendent Carol Comeau said. The district and the nonprofit have yet to work out details, but Cook Inlet wants to start the project this fall. There's a clear need for a fresh approach to teaching Native students. District reports show that Native kids are twice as likely to drop out as other students; their grade-point average is C compared with B- for the district as a whole, and Native high school students earn fewer credits annually than other students. All the efforts to date, such as tutoring, summer school and special programs at two high schools just for Native students, have not closed the gap in achievement between Native students and non-Natives. The 6,200 Native students are the largest minority group in the district, 12.5 percent of total enrollment. About 200 additional Native students enroll each year, reflecting a trend of village families moving into the city. Some new students "are behind our kids right from the beginning," Comeau said. Most Native students do OK in elementary school, but during middle and high school, many do poorly. "You can hear the stress in parents' voices," said Lydia Hays, who is in charge of developing the Partners project for Cook Inlet. Parents tell her: " 'I'm really worried about my son moving from elementary to middle school. He's going to get lost,' " she said. That happened to Renee McCord, an Athabaskan, in high school. She dropped out after her junior year at West. "I skipped classes," said McCord, now 21. "The classes were always overcrowded. There was just not enough help from the teachers." More personal attention, which the Cook Inlet program would bring, might have helped her, McCord said. Instead, she quit, had a baby and earned a GED. Why do so many Native students struggle in Anchorage schools? Some reasons are obvious. A greater percentage of them are poor, and Native families move their children from one school to another more often than other Anchorage families do. Low income and transience are tied to lower achievement, district testing experts say. But there's another important problem, said University of Alaska professor Ray Barnhardt: Schools don't pay adequate attention to a student's culture. The student doesn't feel part of the school and stops going. "We have pretty hard evidence here in Alaska that when schools implement standards for a culturally responsive curriculum, students make the connection" and stay in school, said Barnhardt, a Fairbanks professor specializing in Native education. Parents and teachers work together better if school staffers get to know the family values instead of just expecting parents to come in and support the school's efforts, he said. For example, he said, in the Bering Sea coastal village of Alakanuk teacher turnover was 100 percent for several years in a row. In a desperate move to keep the teachers, the village took the school staff to a subsistence camp for three weeks one year, before school started. "The result was parents got to know teachers on their own terms in their own setting. They began working together on projects everybody could relate to." And teachers began staying on in the village for longer periods, Barnhardt said. Creating that kind of parent-school relationship is easier in a village but can be done in the cities, he said. Barnhardt thinks either of the programs Cook Inlet has considered -- a charter school or providing more personal attention in regular schools -- could improve Native students' success rate. But it will work only if school staffers get to know the Native families and take into account their values and culture. Cook Inlet intends to eventually hire about 30 people, 10 teams of three, and expects to help about 1,000 Native students annually in grades seven through 12. This fall, it will start with two to four teams, at a cost of about $135,000 for each team, Hays said. The ultimate goal is for each of the schools with the largest concentration of Natives -- Clark, Romig and Wendler middle schools and Bartlett, East and West high schools -- to have full-time teams in residence. Four more teams would rotate among the other seven middle and high schools. A counselor and tutor would work with kids individually or in small groups. One team member at each school would do home visits. Cook Inlet, a nonprofit corporation that offers an array of social services to Natives who live in this region, operates on government and private grants. During the past fiscal year, it spent $11 million on education programs, drug and alcohol treatment, welfare assistance and more. |

|

|

|

Cook Inlet Tribal Council |

|

|

||

|

|

||

| Canku Ota is a free Newsletter celebrating Native America, its traditions and accomplishments . We do not provide subscriber or visitor names to anyone. Some articles presented in Canku Ota may contain copyright material. We have received appropriate permissions for republishing any articles. Material appearing here is distributed without profit or monetary gain to those who have expressed an interest. This is in accordance with Title 17 U.S.C. section 107. | ||

|

Canku Ota is a copyright © 2000, 2001 of Vicki Lockard and Paul Barry. |

||

|

|

|

|

|

The "Canku Ota - A Newsletter Celebrating Native America" web site and its design is the |

||

|

Copyright © 1999, 2000, 2001 of Paul C. Barry. |

||

|

All Rights Reserved. |

||