|

|

Canku Ota |

|

|

(Many Paths) |

||

|

An Online Newsletter Celebrating Native America |

||

|

July 27, 2002 - Issue 66 |

||

|

|

||

|

Gold, Greed and Genocide |

||

|

by Shandi

|

||

|

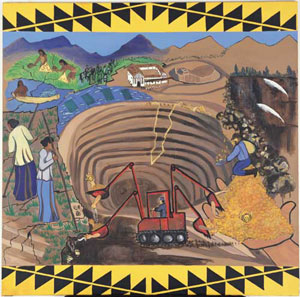

credits: About the

artist: Denise Davis, whose family is from the Maidu tribe of the Sierra

foothills, lives in Chico, California. The design that frames this painting

is a traditional Maidu basket pattern. It was Maidu land on which gold

was originally discovered at the place we now know as Sutter's Mill.

|

I

escape the madness of San Francisco's concrete jungle with road trips

north, squinting my eyes during the car ride to picture what California

may have been before paved streets, smog and gray buildings. Rich fertile

soil, rolling green lands and clear skies for miles ... I breathe in hot

summer air while trying to ignore the fact that the river running alongside

the road on our way to Coyote Valley for the Pomo Bigtime gathering at

Shodokai Casino is polluted beyond repair. I

escape the madness of San Francisco's concrete jungle with road trips

north, squinting my eyes during the car ride to picture what California

may have been before paved streets, smog and gray buildings. Rich fertile

soil, rolling green lands and clear skies for miles ... I breathe in hot

summer air while trying to ignore the fact that the river running alongside

the road on our way to Coyote Valley for the Pomo Bigtime gathering at

Shodokai Casino is polluted beyond repair.

California as it was before white folks arrived - before the greed of the Gold Rush 49ers destroyed traditional people and environment of this land-is what elders see every time they close their eyes. They recall stories of a time when people lived alongside nature, not on top of it. And children listen as stories of their history are passed along through oral tradition. Now Native Californian youth are sharing these stories by traveling throughout the U.S. to speak about their experiences and show documentary films like "Gold Greed and Genocide: Unmasking the Myth of the California Gold Rush." I recently attended a public screening of the film in San Francisco, hosted by the International Indian Treaty Council's Bay Area Indian Youth Mentorship Program, to learn more about a tragic piece of California's bloody history that continues to haunt all who live in the state today (whether they are blissfully ignorant of it or not). The evening began with a prayer song and sage blessing led by Mickey Gemmil, one of the AIM revolutionaries who took back Alcatraz in 1969. Ana Moraga, 19, and Ross Cunningham, 23, two youth who travel throughout the country to promote the film, shared personal stories. Moraga, who is Mayan and from Guatemala, was forced to attend French schools growing up and never learned about her history or culture. She finally had the opportunity to explore her Mayan roots in the U.S. "I feel liberated," she said, her voice shaking. "I felt that my culture was in me, but I couldn't say it and be proud of it. But now I can stand in front of you and say I am proud to be Mayan." Cunningham, who is Pomo and from California, said he always looked to his elders for answers when growing up. They would tell him stories about how the California state government had paid $1 million in 1851 for Indian Scalping Missions. "It was twenty-five cents for a scalp, five dollars for a head," said Cunningham. "It was California state law, enforced by the governor. These are the types of things that were going on during the Gold Rush period." The audience gasped and shook their heads as Cunningham went on to talk about how miners dumped about 7,000 tons of mercury into water regions in California to extract gold from the ore, permanently destroying all water sources in the state. After a few more speakers the film began. It was a roughly shot documentary directed by San Francisco State student Pratap Chaterjee and narrated by Pomo high school student Dalina Duncan. A thumping hip hop soundtrack provided by Bay Area indigenous artists Culture of Rage, DJ Ci Cutz, and Cunningham gave the film an urban feel that contrasted the serene images of river, sky and earth, providing a powerful backdrop for horrific true stories of death and destruction. "Pre-1848 California exists/Clear water streams, fish, green wilderness/The last moment of bliss, last breath of freedom/Greed cries eureka, 49er pirates come," the soundtrack throbbed as black and white images of settlers and mining excavations invaded the screen and what really happened in 1849 was revealed-gold, greed and genocide, slavery, brutality and inhumanity. Over 150,000 indigenous Californians had lived peacefully as fishers, hunters and gatherers before the Gold Rush. But just 20 years after James Marshall discovered yellow metal in the American River at Coloma, there were only 31,000 Californian Indians left. Over 4,000 Native children were sold-$60 for a boy to $200 for a girl (women were raped and abused by the miners)-as 12 billion tons of earth were dug up, river beds were excavated and hillsides were blasted. Elders like Jim Brown, an Elem Pomo from Clear Lake, California, said over 100 tons of toxic mercury waste still lie beneath his traditional homeland. He said his people can't even step foot in the river by his home today because it's so contaminated. All the elders' stories featured in the film were equally shocking, horrifying and upsetting, but the film ended on a positive note, with images of youth and California poppies suggesting hope for the future. "It sounds like a sad story, but it's my history," said Brown. "And I'm going to pass it on."

|

|

|

||

|

|

||

| Canku Ota is a free Newsletter celebrating Native America, its traditions and accomplishments . We do not provide subscriber or visitor names to anyone. Some articles presented in Canku Ota may contain copyright material. We have received appropriate permissions for republishing any articles. Material appearing here is distributed without profit or monetary gain to those who have expressed an interest. This is in accordance with Title 17 U.S.C. section 107. | ||

|

Canku Ota is a copyright © 2000, 2001, 2002 of Vicki Lockard and Paul Barry. |

||

|

|

|

|

The "Canku Ota - A Newsletter Celebrating Native America" web site and its design is the |

||

|

Copyright © 1999, 2000, 2001, 2002 of Paul C. Barry. |

||

|

All Rights Reserved. |

||