|

Although

the caribou Rangifer tarandus is one of Canada's most widely distributed

large mammals, most Canadians know it only as the animal on the 25-cent

piece. Caribou are most familiar to northern Canadians, for many of whom

they are an essential economic resource. The caribou's Micmac name was

"xalibu," meaning "the one who paws," and the present

name is probably a corruption of this word. Although

the caribou Rangifer tarandus is one of Canada's most widely distributed

large mammals, most Canadians know it only as the animal on the 25-cent

piece. Caribou are most familiar to northern Canadians, for many of whom

they are an essential economic resource. The caribou's Micmac name was

"xalibu," meaning "the one who paws," and the present

name is probably a corruption of this word.

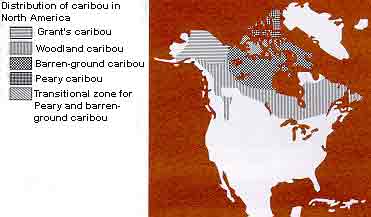

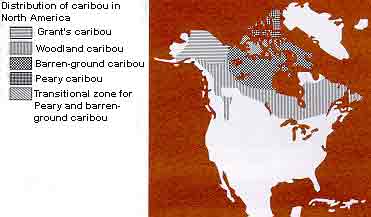

Caribou

are found in Canada from the U.S.-Canada boundary in western Ontario and

British Columbia to northern Ellesmere Island, more than 4000 km north.

Their approximate range is shown on the accompanying map. Some caribou

are forest- and mountain-dwellers; some migrate each year between the

sparse forests and tundra of the far north; others remain on the tundra

all year.

Description

The caribou is

a medium-sized member of the deer family, Cervidae, which includes four

other species of deer native to Canada: moose, elk, white-tailed deer,

and mule deer. All are ungulates cloven- hoofed cud-chewers. However,

only in caribou do both males and most females carry antlers. Caribou

are similar to and belong tothe same species as the wild and domesticated

reindeer of Eurasia.

The

caribou is well adapted to its environment. It has a short, stocky body

and a long dense winter coat which provides effective insulation, even

during periods of low temperature and high wind. The muzzle and tail are

short and well haired. Large, concave hooves splay widely to support the

animal in snow or muskeg, and function as efficient scoops when the caribou

paws through snow to uncover lichens and other food plants. The sharp

edges give firm footing on ice or smooth rock. Caribou are excellent swimmers

and their hooves function well as paddles. In summer, the hooves are worn

away by travel over hard ground and rocks. The

caribou is well adapted to its environment. It has a short, stocky body

and a long dense winter coat which provides effective insulation, even

during periods of low temperature and high wind. The muzzle and tail are

short and well haired. Large, concave hooves splay widely to support the

animal in snow or muskeg, and function as efficient scoops when the caribou

paws through snow to uncover lichens and other food plants. The sharp

edges give firm footing on ice or smooth rock. Caribou are excellent swimmers

and their hooves function well as paddles. In summer, the hooves are worn

away by travel over hard ground and rocks.

A caribou bull (male) in full autumn pelage is an imposing animal with

its rich brown or grey and white pelage, dewlap fringe of white hair flowing

from throat to chest, and great rack of amber-coloured antlers. Adult

bulls generally shed their antlers in November or December, after they

have mated. Cows and young animals carry their antlers much longer, often

through the winter. The growing antlers have a fuzzy covering, called

velvet, which contains blood vessels carrying nutrients for growth.

The

ability of caribou to use lichens as a primary food distinguishes them

from all other large mammals and has enabled them to survive on harsh

northern rangeland. Caribou have an excellent sense of smell, which they

use to locate lichens under the snow.

Caribou

are very curious and hunters have found that by slowly waving their arms,

or bobbing up and down from the waist, they can often attract caribou

to close range.

Races Races

There are three

types of caribou in Canada: woodland, barren-ground, and Peary. A fourth

type, the Queen Charlotte Island race, is extinct. The Queen Charlotte

Island caribou Rangifer tarandus dawsoni was a small, greyish caribou

found only on Graham Island. Little is known of this animal or of the

causes for its extinction, but deterioration of habitat due to climate

change was probably a more important cause than hunting.

The

Peary caribou Rangifer tarandus pearyi is a small, light-coloured caribou

found only in the islands of the Canadian arctic archipelago. Average

weights are 70 kg for bulls and 55 kg for cows. The total population was

estimated at 3300–3600 animals in the late 1980s and was declining.

Peary caribou are listed as threatened by the Committee on the Status

of Endangered Wildlife in Canada (COSEWIC) because of their low overall

numbers.

The

woodland caribou Rangifer tarandus caribou is a large, dark caribou that

is usually found in small herds in (boreal) forests from British Columbia

to Newfoundland. Average weights are 180 kg for bulls and 135 kg for cows.

In mountainous areas of western Canada, woodland caribou make seasonal

movements from winter range in forested valleys to summer range on high,

alpine tundra. Farther east, in the more level areas of boreal forest,

they may move only a few kilometres seasonally from mature forest to open

bogs. The George River Herd, however, is an exception to this pattern

and makes extensive seasonal movements between forested and tundra habitats

in Quebec and Labrador. This herd is currently estimated at over 500 000

animals and is the largest herd of caribou in Canada.

Woodland

caribou became extinct in Prince Edward Island before 1873 and in New

Brunswick and Nova Scotia by the 1920s. Today only a small, relic herd

on the Gaspé Peninsula remains of the maritime woodland caribou

population south and east of the St. Lawrence River. This herd is considered

threatened by COSEWIC. Caribou have also been severely reduced on the

southern edge of their distribution across the rest of Canada and exist

only in small, scattered herds from British Columbia to Quebec. The western

population of woodland caribou is categorized as vulnerable by COSEWIC.

Overhunting in some areas and changes in habitat in others brought about

the decline in numbers. Clearing of land for agriculture has destroyed

caribou habitat. Vast areas of forest have been logged or burned and replaced

by new growth that is much more suitable for moose and deer than for caribou.

The invading deer brought a neurological disease that kills caribou, although

it does not harm the deer. Opportunity for reintroduction of woodland

caribou to parts of its former range are therefore limited.

The

barren-ground caribou is somewhat smaller and lighter coloured than the

woodland caribou and spends much or all of the year on the tundra from

Alaska to Baffin Island. The Alaskan form, Grant's caribou Rangifer tarandus

granti, lives west of the Mackenzie River and the Canadian form Rangifer

tarandus groenlandicus lives to the east. Average weights for the smaller

Canadian form are 145 kg for bulls and 90 kg for cows. Most (about 1.2

million) of the barren-ground caribou in Canada live in five large herds,

which migrate seasonally from the tundra to the sparsely treed northern

coniferous forests, known as taiga. In order, from Alaska to Hudson Bay,

these are the Porcupine Herd, Bluenose Herd, Bathurst Herd, Beverly Herd,

and Kaminuriak Herd. Other barren-ground caribou (about 120 000) live

in smaller herds that spend the entire year on the tundra. Barren-ground

caribou make up the majority of caribou in Canada and are the mainstay

of many northern Amerindian and Inuit communities.

Annual

cycle of barren-ground caribou

The life of a

migratory barren-ground caribou has a fixed annual pattern. Most spend

winter in the taiga, but some always winter on the tundra. Usually the

bulls venture farthest south into the forest where snow tends to be deepest,

and the cows and juveniles remain nearer the tree line. The herds gather

in spring for the migration to the calving grounds and to their summer

range on the tundra.

Barren-ground

caribou are good navigators, unerringly walking hundreds of kilometres

in spring to their relatively small calving areas. They tend to follow

frozen lakes and rivers, open snow-free uplands, and eskers long narrow

hills of soil and rock dumped by glaciers to their destination. Caribou

are able to keep a steady direction across frozen lakes so large that

the opposite shore cannot be seen.

The

pregnant cows lead the spring migration, followed by the juveniles and

the bulls, which tend to lag farther and farther behind. Barren-ground

caribou cows head toward traditional calving grounds to which they return

year after year, even from different wintering areas. About 90 % of adult

cows (3 years old or older) produce calves annually. Most of the calves

are born in a 10-day period in late May or early June.

The

calves are well developed at birth and are able to travel within a few

hours. They start to graze during their first weeks, although at that

stage they can digest only milk. The cows and calves soon move to areas

where fresh-growing feed is becoming abundant. During summer they are

often harassed by hordes of mosquitoes, warble flies, caribou nostril

flies and, in some areas, black flies. Sometimes the agitated animals

will run for many kilometres, stopping to rest only when exhausted or

when high winds temporarily disperse the insects. Running from insects

places great energy demands on the caribou, and may retard their rate

of growth by temporarily reducing their foraging.

In

July the herds start to move en masse and feed on flowers, grasses, and

leaves of shrubs. The mating season, the rut, occurs in late October and

early November. By late September the herds, fat and in good condition

are arriving in pre-rutting areas. Bulls spar a great deal and sometimes

fight for possession of cows.

The

migration routes have always been so well established that, in past years,

Native hunters lay in wait for caribou at places where they would cross

lakes or rivers. Occasionally, however, the caribou did change their migration

routes, and hunters and their families located near the traditional migration

path faced starvation.

Enemies

The wolf is a

natural predator of the caribou. Wolf packs follow the migrating herds

from summer to winter range and back. Caribou are relatively free from

this predator only during calving time, when the breeding wolves are raising

their young in areas distant from the calving ground. A wolf requires

food equivalent to 11-14 caribou a year, and it may kill that many. Most

wolves also hunt mice, lemmings, other small mammals, and birds. Wolves

cannot run as fast for as long as healthy caribou, especially in deep

snow, so wolves often chase a caribou in relays, or wait in ambush for

an unwary victim.

Wolves

have a culling effect on the caribou population, as they kill the aged,

injured, or young weak animals when they are available. Most biologists

agree that the relationship between wolf and caribou benefits both. Certainly

the relationship has evolved and lasted over tens of thousands of years.

The

human being, however, is the greatest of all caribou predators. Many Canadian

Amerindians and Inuit based their culture on the caribou, and could not

have survived in the north without them. Some tribes were nomadic, and

followed the herds year round; others lived on caribou for part of the

year. Caribou provided food, clothing, and shelter: bones were made into

needles and utensils, antlers into tools, and the sinew into thread; the

fat provided fuel and light; the skin was made into light, warm clothing

and tent material; and the flesh fed people and dogs.

Conservation

The take by hunters

using primitive weapons was in balance with the numbers of caribou. The

introduction of the rifle by trappers and traders, however, made it possible

to kill large numbers. It is thought that in the three decades before

1950, kill by humans ranged from 100 000 to 200 000 a year. In some years,

this was more than the animals' natural increase.

Originally

there were probably at least three million barren-ground caribou. Their

numbers began to decline shortly after Europeans arrived in the North

armed with rifles and seeking furs. By 1949, when aerial survey methods

made it possible to count caribou for the first time, there were only

about 750 000 animals. Despite federal, territorial, and provincial government

attempts to reduce overhunting by supervising hunts and enforcing game

regulations, and in spite of an emergency wolf-control program, the population

continued to fall, to about 350 000 by 1955. For a time there was fear

that the caribou might, like the plains bison, approach extinction. However,

a 1967 range-wide survey by Canadian Wildlife Service biologists showed

that the decline had stopped. Barren-ground caribou now number about 1.3

million.

Exploration

and settlement of the north were possible because caribou provided food.

Today, caribou are still an economical source of meat because transporting

food into the north is expensive. The vast herds of migrating caribou

present a wildlife spectacle unequalled on this continent and, as an attraction

to naturalists, photographers, and sport hunters, could contribute to

a tourist industry in the north. Wisely used, caribou can be a continuing

economic resource in the North.

|

Once

upon a time, in a camp near Great Slave Lake, there were no caribou

to kill. For days and days the families went without food. Everyone

was very hungry and weak.

Once

upon a time, in a camp near Great Slave Lake, there were no caribou

to kill. For days and days the families went without food. Everyone

was very hungry and weak.  While

the people were talking, a man named Make-Bone said he would follow

the raven the next time he left their camp. So everyone returned

home, to wait for the raven to appear. The raven visited the camp

again the next day, not knowing about the plan the people had decided

upon. As usual, he entered each tent looking for a possible meal.

While

the people were talking, a man named Make-Bone said he would follow

the raven the next time he left their camp. So everyone returned

home, to wait for the raven to appear. The raven visited the camp

again the next day, not knowing about the plan the people had decided

upon. As usual, he entered each tent looking for a possible meal. "I

can see him now," cried Make-Bone. "He's landing near a hill. Let's

follow him there!" Everyone started walking through the forest to

find the raven. It was a long walk and everyone became very tired.

Finally they arrived at the hill where Make-Bone had last seen the

raven.. At first they didn't see any sign of the bird. Then suddenly

they noticed a big spruce hut nearby. Quickly the people surrounded

the lodging. A wolf, who happened to appear then, offered to enter

the hut to see what was inside.

"I

can see him now," cried Make-Bone. "He's landing near a hill. Let's

follow him there!" Everyone started walking through the forest to

find the raven. It was a long walk and everyone became very tired.

Finally they arrived at the hill where Make-Bone had last seen the

raven.. At first they didn't see any sign of the bird. Then suddenly

they noticed a big spruce hut nearby. Quickly the people surrounded

the lodging. A wolf, who happened to appear then, offered to enter

the hut to see what was inside. "Who

will enter the hut to spy on the raven?" the crowd asked. This time

a fox offered to help. Before he went in, he told the people to

put all the children on a pole rack, where they would be safe. Then

the fox told everyone to stand nearby. "Be ready to start spearing,"

he said. When the people were ready, the fox entered the hut. Once

inside, he brushed the fire with his bushy tail. This made large

clouds of smoke. Quickly he trotted outside with a trail of smoke

following him. Everyone waited patiently.

"Who

will enter the hut to spy on the raven?" the crowd asked. This time

a fox offered to help. Before he went in, he told the people to

put all the children on a pole rack, where they would be safe. Then

the fox told everyone to stand nearby. "Be ready to start spearing,"

he said. When the people were ready, the fox entered the hut. Once

inside, he brushed the fire with his bushy tail. This made large

clouds of smoke. Quickly he trotted outside with a trail of smoke

following him. Everyone waited patiently. Although

the caribou Rangifer tarandus is one of Canada's most widely distributed

large mammals, most Canadians know it only as the animal on the 25-cent

piece. Caribou are most familiar to northern Canadians, for many of whom

they are an essential economic resource. The caribou's Micmac name was

"xalibu," meaning "the one who paws," and the present

name is probably a corruption of this word.

Although

the caribou Rangifer tarandus is one of Canada's most widely distributed

large mammals, most Canadians know it only as the animal on the 25-cent

piece. Caribou are most familiar to northern Canadians, for many of whom

they are an essential economic resource. The caribou's Micmac name was

"xalibu," meaning "the one who paws," and the present

name is probably a corruption of this word. The

caribou is well adapted to its environment. It has a short, stocky body

and a long dense winter coat which provides effective insulation, even

during periods of low temperature and high wind. The muzzle and tail are

short and well haired. Large, concave hooves splay widely to support the

animal in snow or muskeg, and function as efficient scoops when the caribou

paws through snow to uncover lichens and other food plants. The sharp

edges give firm footing on ice or smooth rock. Caribou are excellent swimmers

and their hooves function well as paddles. In summer, the hooves are worn

away by travel over hard ground and rocks.

The

caribou is well adapted to its environment. It has a short, stocky body

and a long dense winter coat which provides effective insulation, even

during periods of low temperature and high wind. The muzzle and tail are

short and well haired. Large, concave hooves splay widely to support the

animal in snow or muskeg, and function as efficient scoops when the caribou

paws through snow to uncover lichens and other food plants. The sharp

edges give firm footing on ice or smooth rock. Caribou are excellent swimmers

and their hooves function well as paddles. In summer, the hooves are worn

away by travel over hard ground and rocks. Races

Races