|

|

Canku Ota |

|

|

(Many Paths) |

||

|

An Online Newsletter Celebrating Native America |

||

|

February 7, 2004 - Issue 106 |

||

|

|

||

|

Students Learn Blackfeet |

||

|

by Peter Johnson Great

Falls Tribune Staff Writer

|

||

|

credits: Tribune

Photo by Stuart S. White

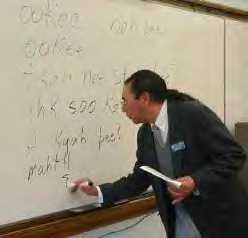

Instructor Klane King writes a conversation during his Blackfeet language class at Great Falls High. |

|

It's a heady experience for King, who learned Blackfeet from his parents as a preschooler in southern Alberta, only to have boarding school teachers try to drum it out of him by whacking his wrists with a yardstick. "I almost forgot the basics of my native tongue," he said. But King had the last say. After college, he came home to the Blood Reserve, as reservations are known in Canada, and started a video production company that specialized in features about Blackfeet elders and legends. Teachers used many of those videos in classrooms of the reservation schools, which had reformed and stressed the importance of Blackfeet culture and language. Since mid-January King has been teaching an introductory Blackfeet class at both Great Falls and C.M. Russell high schools. It's the only Indian language class being taught at a nonreservation Montana high school. The Great Falls district offered a similar intro class to the Cree language three years ago. It was dropped after three semesters when enrollment tapered off. This semester, 23 GFH students and 11 CMR students are taking the class. There are 1,243 Indian students in the Great Falls public schools, about 11 percent of the total, said Assistant Superintendent Dick Kuntz, who was instrumental in starting and renewing the Indian language classes. The district has reduced its Native American dropout rate from a sky-high 80 percent to a state low 10 percent in the 30 years it has had an Indian Education Program featuring tutoring and home counseling, Kuntz said. But that's still about four times the dropout rate for the entire student body. "Any way you can help Native American kids identify with their culture, you've given them another incentive to stay in school," Kuntz said. "And if we get them coming to school every day, they'll do better in their other subjects, too." Great Falls High School Principal Fred Anderson said school officials hope to sustain interest this time by adding more advanced classes if enough students want to keep going. "I think it's an excellent class that will provide an opportunity for both Native American and other students to increase their cultural awareness," Anderson said. He was enthralled after hearing King describe the Blackfeet's original territory, which sprawled from present-day Edmonton to Yellowstone Park, between the Rockies and eastern Montana. "Window

to another culture" The new language class is not all that the district is doing. This year Great Falls sophomores are required to take a Montana civics class divided evenly between tribal government and nontribal government. Next fall high school students can take an optional class that gives an overview of the history and culture of Montana's 11 Indian tribes. "I'm glad to see them start teaching the language here," said Jewell Snell, 65, who with her husband, Frank, is raising four school-age grandchildren. "A lot of people my age never had the chance. The government sent us from the Blackfeet Reservation in Montana to a boarding school in Oregon where nobody spoke our language." "I learned a little bit of Blackfeet from my mother and aunts, but not a lot," said parent Mary Marceau, 37. "I think Indian kids should be able to learn their language and cultural background, but it's harder in an urban setting off the reservation." "I knew a few Blackfeet words, but am learning a lot more," said her son, GFH sophomore Ché Marceau, 15. "It's easy the way Mr. King teaches with repetition and stories." "I've spent half my time growing up in Great Falls and half in Browning, so I learned a few basic words from my grandparents," said GFH junior Roger Cruz, 17. "I wanted to learn more about my culture, and the class is already helping. It's the class I most look forward to every day." "I grew up in Great Falls and didn't know any Blackfeet," said freshman Virginia Yazzie, 16. "I'm looking forward to going to a powwow some time and striking up a conversation in Blackfeet." GFH senior Joe Eagleman, 17, is a senior of Chippewa-Cree descent. "This (Blackfeet class) is learning about another Indian culture that is like mine in some ways but different," he said. "It can be hard starting from scratch with an unwritten language." One-quarter of the Blackfeet language students at both schools are non-Indian. Exchange

student interested "I really like languages and in Europe we're required to take four," she said. "I want to become an anthropologist and this class is great, because I'm learning about a culture I knew nothing about." GFH senior Josh Werkheiser, 17, also is a language buff, and said it's not hard to learn a new language once you realize that internal English rules do not apply. "It's definitely been fun to start learning the Blackfeet language and culture," he said. King stressed that Blackfeet should be spoken "in a flat and low tone, with no musical lilts up and down." There are other differences between English and Blackfeet, too, he said. "In the United States and Canada people almost seem to panic when there is a lapse in conversation," he said. "In Blackfeet, it's common to pause every now and then, maybe take a swig of coffee, and let companions absorb what's been said." King also thinks the Blackfeet language has more specific nouns, with some words taking the place of whole sentences in English. For instance, the word "iniwa" means buffalo. When Blackfeet add a long, tongue-twisting suffix, the word signifies "the buffalo are rumbling toward you with their back, dew claws clicking." You can almost feel the dust and better scramble for cover. But King, 50, was at the tail end of the similar Canadian and U.S. government practices of sending Native American kids to boarding schools where they were directly or indirectly discouraged from using their own language. Starting at age 6, he spent weekdays at a boarding school across the reservation from his home. Teachers demanded that students speaking Blackfeet place their hands on the table and smacked their wrists. He said they drove the colorful language from his lips, and almost from his memory, but not from his heart. King attended college in Edmonton, picking up degrees in Canadian studies and Native communication, including broadcast and video production skills. But the instructors who spoke a Native language were Cree, he said. When he returned home he remembered how rich his native tongue and traditions were when he began making videos of tribal elders. King moved to Great Falls in 2000, where he has been a volunteer cameraman for the public access television channel and a disk jockey for KGPR, the public radio station. Offer

to teach King has several goals for his students. He wants to teach them enough conversational Blackfeet so they can walk up to tribal elders and politely chat. He also will teach them a few Blackfeet meditations, thanking the Creator and asking for blessings. Last week, King chanted his brief, eloquent personal song for the students, suggesting if they listen carefully they can catch a rhythm and make their own song to see them through adversity. "Mine is a really sweet and calming little ditty that came to me one time," he said, quipping: "And there's no copyright infringement worries to prevent me from singing it over and over." |

|

|

www.expedia.com |

|

|

||

|

|

||

| Canku Ota is a free Newsletter celebrating Native America, its traditions and accomplishments . We do not provide subscriber or visitor names to anyone. Some articles presented in Canku Ota may contain copyright material. We have received appropriate permissions for republishing any articles. Material appearing here is distributed without profit or monetary gain to those who have expressed an interest. This is in accordance with Title 17 U.S.C. Section 107. | ||

|

Canku Ota is a copyright © 2000, 2001, 2002, 2003, 2004 of Vicki Lockard and Paul Barry. |

||

|

|

|

|

The "Canku Ota - A Newsletter Celebrating Native America" web site and its design is the |

||

|

Copyright © 1999, 2000, 2001, 2002, 2003, 2004 of Paul C. Barry. |

||

|

All Rights Reserved. |

||

Students

in Klane King's Great Falls language classes enjoy reciting everyday

phrases they've learned in Blackfeet and listen eagerly as their

teacher tells them how Native American songs, games and dances

came to be.

Students

in Klane King's Great Falls language classes enjoy reciting everyday

phrases they've learned in Blackfeet and listen eagerly as their

teacher tells them how Native American songs, games and dances

came to be.