|

Canku Ota

|

|

|

(Many Paths)

|

||

|

An Online Newsletter

Celebrating Native America

|

||

|

May 1, 2009 - Volume

7 Number 5

|

||

|

|

||

|

Tribal Members Recruited Into Medical Fields

|

||

|

by William Hermann - The Arizona Republic

|

||

|

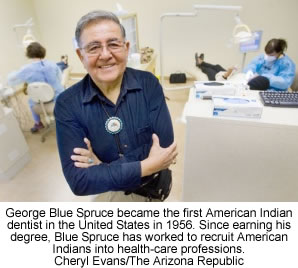

credits: photo by Cheryl

Evans - The Arizona Republic

|

|

For a Navajo student, it was learning to believe that he could become a doctor when every other kid in his graduating class was going to a trade school. The need for Native Americans in the health-care professions has never been greater, but the obstacles standing between them and medical degrees are often daunting, if not overwhelming. George Blue Spruce knows those obstacles firsthand and has spent a lifetime helping others overcome them. Blue Spruce, the nation's first American Indian dentist, is an assistant dean at A.T. Still University in Mesa, where he is helping tribal members enter the world of medicine. At 78, Blue Spruce has a long and distinguished resume. He founded the Society of American Indian Dentists and was assistant U.S. surgeon general from 1981 to 1986. He also wrote the original draft of the Indian Health Care Improvement Act in Title 1 of federal statutes. Now "retired," he is pursuing what he calls his true life's work: traveling the nation to tell young American Indian men and women that the medical professions need them, and perhaps more importantly, that their people need them to be in the medical professions. Largely through his efforts, A.T. Still claims more American Indian dentists in training than any other school in the country. In addition, American Indians are being educated in osteopathic medicine and as physician's assistants and athletic trainers. Since Still's dental college opened in 2002, eight American Indians have graduated with dental degrees, and 12 are "in the pipeline," according to Carol Grant, Still's director of American Indian Health Professions. The numbers tell the story of the need. With fewer than 150 American Indian dentists in the country, that means there is roughly one for every 32,000 American Indians, Grant said. The rate among the rest of the population is about one to every 1,200 people. According to Frank Ayers, dean of student affairs at Creighton University's School of Dentistry in Omaha, Neb., the need for Native American dentists is desperate, particularly in remote reservation areas where there are few health-care resources. "A report on oral health issued in 2000 by the American Dental Association showed that among Native American children, tooth-decay rates are four times higher than the general population," Ayers said. "Native American communities have very great needs for dental and medical services and little access to those services." Ayers said that every year, the nation's 56 dental schools "average only about 30 Native American students enrolling in dental schools, and that's not anywhere near enough to meet the needs of Native American communities." Ayers said the key to delivering dental care to Native American communities is recruiting dental students from those communities. "If a student has a strong tribal affiliation when you bring them into the profession, they are much more likely to return to the reservation and help their people," he said. The problem of dental care on reservations is so acute that a bipartisan bill, the Native American Full Access to Dental Care Act, was introduced in Congress in 2007 to address the situation, but it eventually died in committee. But what Congress couldn't get done, Blue Spruce hopes to do, even if only one student at a time. At A.T. Still University, Grant credits Blue Spruce with persuading hundreds of American Indians to seek careers in the health professions. "He goes everywhere, to conferences, to schools, and his message to young people is that 'you can do this, and you are needed,' " Grant said. "Dr. Blue Spruce is a very humble, quiet man, but when he speaks, he does so with authority and people listen." Blue Spruce does exude a quiet, even humble demeanor, but he is matter-of-fact about his own story. His parents were members of the Pueblo tribe of New Mexico and lived near Santa Fe. He attended the Santa Fe Indian School and got his DDS degree from Creighton University. "It all begins with the family, and it was the encouragement of my mother and father who grew up not reading, writing or speaking English," Blue Spruce said. "Yet they saw that for me to be successful in the dominant society, I needed that piece of paper, that piece of character, called a college degree." When Blue Spruce got his DDS in 1956, he began a practice, but he also began talking to other American Indians about why they should go into medicine. "I was the first Indian with a dental degree, and I recruited the young man who became the second," Blue Spruce said. "I haven't stopped recruiting since then. Now we have about 145 American Indian dentists. "I knew that for so many American Indians there is a lack of parental support and often no support from the extended family or from the tribe. And counselors in our Indian communities too often talk to students about a marketable skill right out of high school and not enough about going to college." Rowin Begay, 30, a first year osteopathic medicine student at A.T. Still who is from Rough Rock on the Navajo Reservation in northern Arizona, says his friends didn't really think of college. "In high school," Begay said, "my friends were interested in basketball, and after high school, a job as a carpenter, a welder." He says that he was fortunate to have a family that pressed him to better himself, but even with that support, there have been challenges in medical school that others don't face. "There are cultural things. . . . I've had to work hard to learn to be assertive, to speak publicly, to put myself forward," he said. "That 'being assertive' may be hardest because being quiet and respectful and not putting yourself forward is what we're taught as young people," Begay said. Alyssa Fredericks, 23, is getting an advanced degree as an athletic trainer and came to A.T. Still from Kykotsmovi on the Hopi Reservation in Arizona. She, too, has had to deal with cultural hurdles. "I've had to learn to live in two worlds: the one I was raised in and the one I'm living in now. Things you might not think about come up. When I had to deal with a cadaver, which is a huge cultural problem for a Hopi, I needed (a person who understood) what I was dealing with." Grant credits Blue Spruce with helping find - and keep - students like Fredericks and Begay. "He creates a sense of family when they come here, and he mentors them and advises them. He takes them under his wing and walks them through the whole system," Grant said. Fred Hubbard, executive director of the Arizona Advisory Council on Indian Health Care, said Blue Spruce's work has not only meant nationwide progress in improving health care for American Indians, but also "making significant contributions to what needs to happen in educating American Indian young people." Hubbard added that Blue Spruce "helps them understand what they will experience when they go off the reservation and come to a large educational institution - not just at A.T. Still - and he helps them understand what they need to anticipate." Student Nicole Gore, 39, next month will graduate and become the first member of the Crow tribe with a degree in dentistry. She says that just as she was mentored when she came to the university, so she has become a mentor to others, following the example Blue Spruce has set. "We know that Dr. Blue Spruce will not always be here, and we know that what he has done needs to go on," Gore says. "I hope to continue to mentor young people; I hope to emulate what Dr. Blue Spruce has done, and many of us feel the same way." |

|

|

||

|

|

||

| Canku Ota is a free Newsletter celebrating Native America, its traditions and accomplishments . We do not provide subscriber or visitor names to anyone. Some articles presented in Canku Ota may contain copyright material. We have received appropriate permissions for republishing any articles. Material appearing here is distributed without profit or monetary gain to those who have expressed an interest. This is in accordance with Title 17 U.S.C. Section 107. | ||

|

Canku Ota is a copyright ©

2000, 2001, 2002, 2003, 2004, 2005, 2006, 2007, 2008, 2009 of Vicki

Barry and Paul Barry.

|

||

|

|

|

|

The "Canku

Ota - A Newsletter Celebrating Native America" web site and

its design is the

|

||

|

Copyright ©

1999, 2000, 2001, 2002, 2003, 2004, 2005,

2006, 2007, 2008 of Paul C.

Barry.

|

||

|

All Rights Reserved.

|

||

For

a young Hopi medical student, the problem was overcoming her culture's

view of handling a dead body.

For

a young Hopi medical student, the problem was overcoming her culture's

view of handling a dead body.