|

Canku Ota

|

|

|

(Many Paths)

|

||

|

An Online Newsletter

Celebrating Native America

|

||

|

NOVEMber 2013 - Volume

11 Number 11

|

||

|

|

||

|

Native History: How

Natives Got Railroaded By The Medicine Lodge Treaty

|

||

|

by Christina Rose -

Indian Country Today Media Network

|

||

|

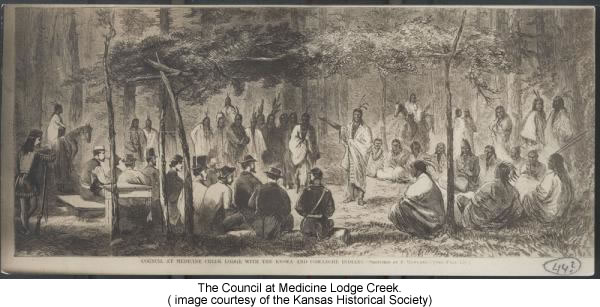

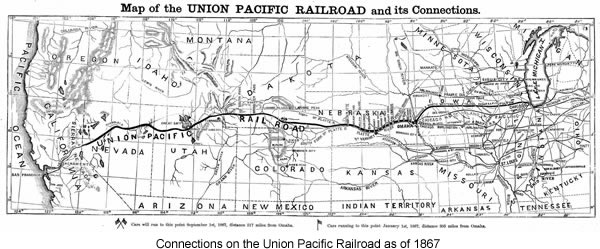

This Date in Native History: On October 21, 1867 the Medicine Lodge Treaty was signed in Kansas. Michael Stewart, a Native history expert with Haskell Indian Nations University, said the treaty was important to the U.S. and development of the railroads because of Westward Expansion. "The question was, ‘How do we isolate the tribes?' The tribes had released their treaty lands to the railroads, which needed a 20-mile leeway, and the railroad cut through the hunting areas. The lines followed the traditional routes to California, and brought in more immigrants, building hostilities with Indians, and that's where politics came into it... if you get the railroad in your state, your state becomes more important."

At the end of the Civil War, Westward Expansion pushed into Kansas, where reservations had already been established, but not enforced. Poor land quality kept the settlers out until new farming techniques and the Union Pacific Railroad brought an onslaught of immigrants, intent on holding onto the land against any claims by the Indians. Newspaper reports exaggerated "Indian depredations" and the governor of Kansas led the pack by demanding that the U.S. Department of War send military assistance to deal with an almost imaginary problem. The Union Pacific Railroad also complained that the attacks by Indians were so bad, no one could work on the railroad. However, according to a 1932 report by the Kansas Historical Society, it was later revealed that work had halted on the railroad because the soil was so muddied after heavy rains, and the Union Pacific was willing to pay copy million to get out of their contract.

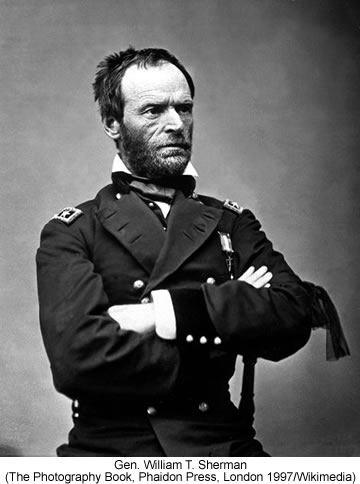

Gen. William T. Sherman, of Civil War fame, found the claims of the Kansas governor and Union Pacific hard to believe. In his opinion, every western settlement was nervous about Indians and asking for assistance. He refused to send troops to Kansas, but against his better judgment, agreed to send massive amounts of ammunition to arm the locals and form the 18th Kansas Cavalry. The Kansas Historical Society report said that Sherman had been touring Kansas and Colorado in the fall of 1866 and had not heard of any complaints about Indians aside from rumors. He reportedly said, "These are all mysterious, and only accountable on the supposition that our people out West are resolved on trouble for the sake of the profit resulting from the military occupation."

At the same time, two newspapers, in a rally of competition and a ruse to gain readership, printed rumors of Indian attacks as fact. Stories from the newspaper, The Leavenworth Commercial were republished by eastern papers as true, furthering negative attitudes against the tribes. Anderson said the tactics were not unusual. "A lot of it was manufactured crisis in the name of progress or profit. It definitely had a bigger hand in shaping what actually happened." After Kansas Governor Samuel J. Crawford had amassed 11,000 rounds of ammunition, four regiments of 358 officers and enlisted men set out to defend their towns based on fears, phobias, and perhaps a desire to make a name for themselves. Four years after the Sand Creek Massacre, theses troops approached a quiet band of Cheyenne and Sioux who had waved a white flag and requested peace. Still, perhaps in a move of intimidation, the troops set up their camp near the tribes and caused them to flee in the night, the Kansas Historical Society report noted. Sherman held his opinion that no actions should be taken against the tribes until they met with the Cheyennes, and finally the U.S. Peace Commission established a treaty meeting with the tribes, even as General Sherman knew it would take years to meet the treaty obligations. Estimates of between 5,000 to 15,000 Cheyenne, Arapahoe, Comanche, Kiowa, and Kiowa-Apache camped in the area, and on October 21, the first treaty was signed by the Comanche, Kiowa and Apache. A week later the Cheyennes and Arapaho agreed to sign as well. The two treaties required that there be no opposition to the railroads and that the tribes relinquish many of their land claims and return to the already established reservations, and the tribes would receive a large reservation and supplies, and the right to hunt south of the Arkansas River as long as buffalo was plentiful there. The U.S. promised that no white settlements could occupy the area of the Arkansas River and the southern boundary of Kansas for three years. But, "There were a lot of violations of the treaties, and for different reasons," Anderson said. "This new rush of re-settlers came into the area competing in a hostile way to the Indians who remained. There was corruption among the Indian agents and there was a re-removal. They were not only dealing with indigenous Kansas groups who had been free ranging on the Plains, but there were other groups who had been pushed out of the east, like the Pottawattomi and the Sac and Fox. This process of treaty making went back to the 1850s and trying to figure out what to do with them." In the end, the treaties were not recognized by other Plains tribes, and while there were no real large-scale revolts, the result was that previous peace had been disturbed and tensions again flared throughout the Plains. The 1932 report by the Kansas Historical Society is surprisingly balanced for that period of time. Eric Anderson, Ph.D. of American History, specializing in American Indian history and instructor at Haskell Indian Nations University in Kansas, said, "In 1932, that's only four years after the Meriam Report. There was sympathy in the country, and in 1864 the Sand Creek Massacre, then dial it back to Medicine Lodge; 70 years later there was a cry among the eastern elite about the treatment of the Indians." |

|

|

||

|

|

||

| Canku Ota is a free Newsletter celebrating Native America, its traditions and accomplishments . We do not provide subscriber or visitor names to anyone. Some articles presented in Canku Ota may contain copyright material. We have received appropriate permissions for republishing any articles. Material appearing here is distributed without profit or monetary gain to those who have expressed an interest. This is in accordance with Title 17 U.S.C. Section 107. | ||

|

Canku Ota is a copyright ©

2000 - 2013 of Vicki Williams Barry and Paul Barry.

|

||

|

|

|

|

The "Canku

Ota - A Newsletter Celebrating Native America" web site and

its design is the

|

||

|

Copyright ©

1999 - 2013 of Paul C. Barry.

|

||

|

All Rights Reserved.

|

||

Sherman

later expressed that except for a few raids by youthful warriors,

"almost every Indian agent says his particular Indians are at home

and at peace."

Sherman

later expressed that except for a few raids by youthful warriors,

"almost every Indian agent says his particular Indians are at home

and at peace."