|

Canku Ota

|

|

|

(Many Paths)

|

||

|

An Online Newsletter

Celebrating Native America

|

||

|

December 2014 - Volume

12 Number 12

January 2015 - Volume 13 Number 1 |

||

|

|

||

|

Ancient, Melting

Ice Patches On Mountain Slopes Yield Clues To Athabascan History

|

||

|

by Linda Weld - Alaska

Native News

|

||

|

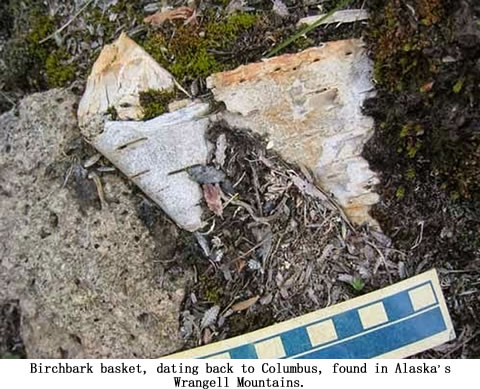

In Alaska, a still-cold part of the world, there remain many glaciers. And, many other icy geological features: Including gigantic “ice fields” and smaller permanent “ice patches.” An ice patch is an isolated patch of ice in the lee of a slope, made by drifting snow that is at an altitude where it never melts. Ice patches are often high in the treeless mountains, but not so high that animals and people can’t reach them. (Ice patches can be seen in the Alaska summer from the road along the lower Richardson Highway, on the way to the coastal town of Valdez) Because “ice patches” remain all summer long, they are places caribou can escape the hordes of insects that populate the tundra — and where they can cool down. Ancient hunters, aware of the cyclical patterns of Alaska’s wildlife, and the way that they are funneled along the same basic routes — year after year — followed their prey to the ice patches. At the ice patches, these long-ago hunters killed animals, and stayed there in the summer, waiting for other game to show up. As all of us humans tend to do, the hunters left behind their everyday litter on the ice. This included arrowheads, pieces of wooden arrow shafts, broken birchbark baskets, carved antlers, and even sinew that was used to lash an antler projectile to an arrow shaft: The fabric of their lives. Generally, the “stuff” that ancient Athabascans in Alaska used and discarded has been completely recycled by the earth. It’s not particularly solid material, but is more likely to be made of “biodegradables” — leather, feathers, wood pieces, antlers (which are commonly gnawed by voles for the calcium), and even a thin piece of copper, fashioned into an arrowhead. At the ice patches, these ancient people’s litter fell down through the snow, protected by the ice, as if in a giant freezer. Recently, the ice patches have begun to melt. And the items that are in them — the wood, and birchbark and sinew, even an arrow feather — have dropped down onto the surface of the tundra. Archaeologists have gone searching for these items in the Wrangell Mountains. And, amazingly, they have found quite a bit of hitherto unseen evidence of how people lived up to 3,000 years ago. Some of the items are very old. The pink-and-white piece of birchbark basket — its sewing holes as fresh and clear as if it were made in the nearby village of Chistochina yesterday — dates back to the days of Columbus. Other items date back to the Middle Ages, and to almost a thousand years before Christ. “Ice Patch Archaeology” is a new and exciting field of research that reveals a startling look at a very fragile, and difficult-to-chronicle way of life, high in the Alaska arctic. The Wrangell-St. Elias project was undertaken by James Dixon,

of the University of New Mexico, who worked with the Wrangell-St.

Elias National Park and the Ahtna Heritage Foundation. Local Ahtna

people accompanied the archeologists, and helped locate artifacts.

Local people who worked with Jim Dixon through the Ahtna Heritage

Foundation included: On October 30th, 2014 there was a special “Coming Home” celebration, in which people from the University, the National Park, the Ahtna Heritage Foundation and the Alaska and Copper River communities showed up to welcome several of the artifacts to a new home at the Ahtna Cultural Center – C’ek’aedi Hwnax ‘Legacy House’ – on the grounds of Wrangell-St. Elias Park’s visitor center complex in Copper Center, Alaska. |

|

|

|

||

|

|

||

| Canku Ota is a free Newsletter celebrating Native America, its traditions and accomplishments . We do not provide subscriber or visitor names to anyone. Some articles presented in Canku Ota may contain copyright material. We have received appropriate permissions for republishing any articles. Material appearing here is distributed without profit or monetary gain to those who have expressed an interest. This is in accordance with Title 17 U.S.C. Section 107. | ||

|

Canku Ota is a copyright ©

2000 - 2014 of Vicki Williams Barry and Paul Barry.

|

||

|

|

|

|

The "Canku

Ota - A Newsletter Celebrating Native America" web site and

its design is the

|

||

|

Copyright ©

1999 - 2014 of Paul C. Barry.

|

||

|

All Rights Reserved.

|

||

WRANGELL

MOUNTAINS: Over 14,000 years ago, much of North America was covered

in ice, starting at the Alaska Range, and moving down all the way

to what are now the cities of Chicago and New York. The ice was

very thick — miles thick. Then, it abruptly melted over much

of the northern hemisphere. Except in parts of Alaska. Around 10,000

to 12,000 years ago, the ice in Alaska was close to its present

configuration, with high mountain glaciers surrounding the Copper

River Valley.

WRANGELL

MOUNTAINS: Over 14,000 years ago, much of North America was covered

in ice, starting at the Alaska Range, and moving down all the way

to what are now the cities of Chicago and New York. The ice was

very thick — miles thick. Then, it abruptly melted over much

of the northern hemisphere. Except in parts of Alaska. Around 10,000

to 12,000 years ago, the ice in Alaska was close to its present

configuration, with high mountain glaciers surrounding the Copper

River Valley.