|

Canku Ota

|

|

|

(Many Paths)

|

||

|

An Online Newsletter

Celebrating Native America

|

||

|

July 2017 - Volume 15

Number 7

|

||

|

|

||

|

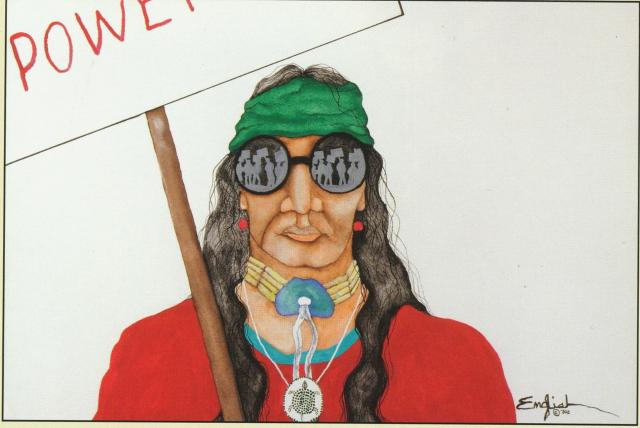

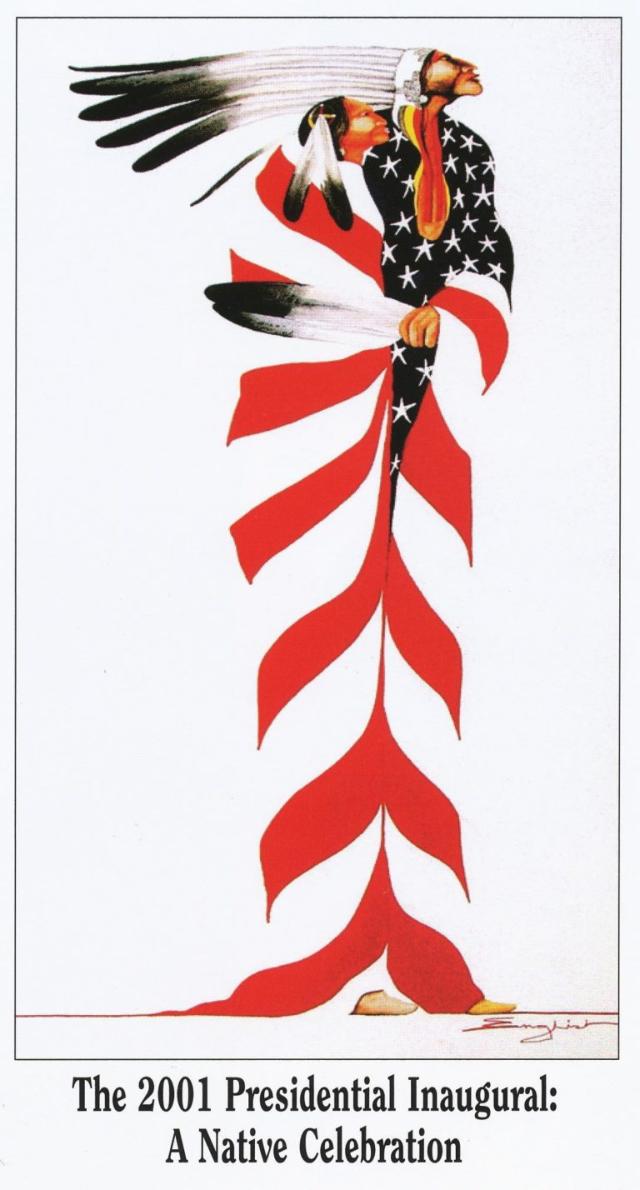

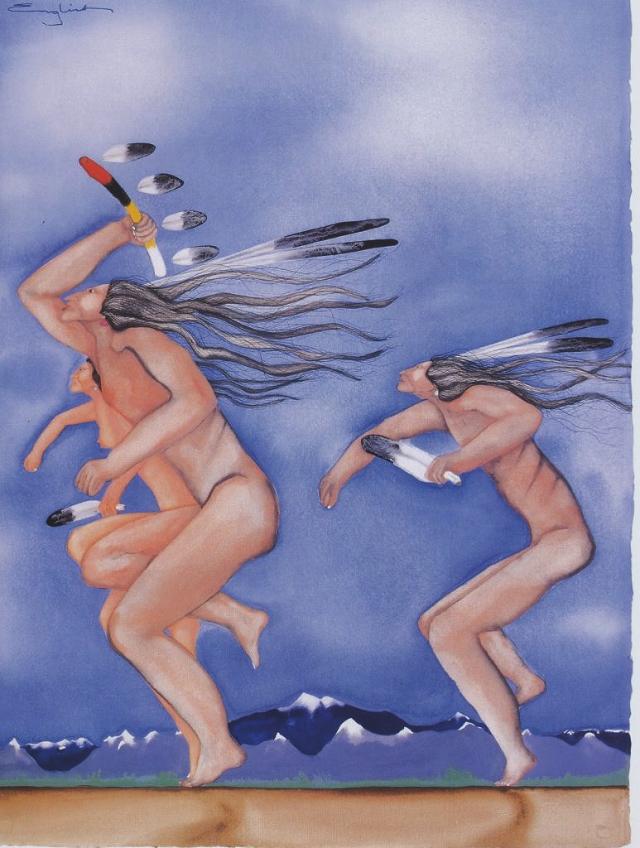

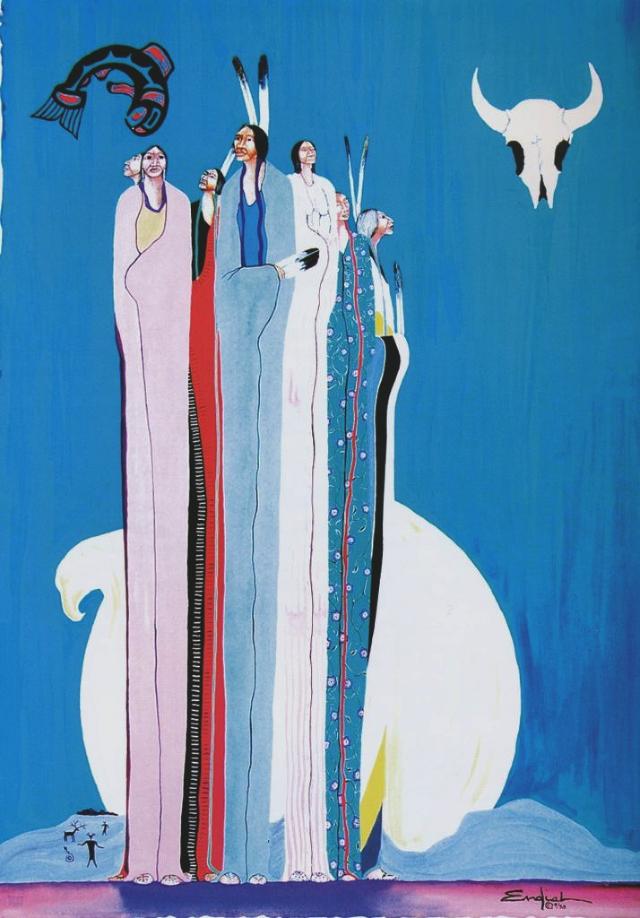

The Previously Undiscovered

Painted Treasures Of Native Artist Sam English

|

||

|

by Tom Kanthak - Indian

Country Today

|

||

|

Seventy-five

year old Native American artist Sam English has over 65 paintings

and lithograph prints waiting to be seen by the public

Tucked away in a storage facility in Albuquerque are over 65 paintings and lithograph prints created by 75-year-old Native American artist, activist and aesthetic healer Sam English. Sam English is the son of Ojibwe/Anishinaabe/Chippewa parents; a mother from the Turtle Mountain people of North Dakota (where he is enrolled) and a father from the Red Lake Nation of Minnesota. He has spent most of his life in the Southwest and currently lives in Albuquerque. Although his early life was spent in middle-class obscurity, disconnected from his Northern Woodlands heritage, his career documents many of the significant moments in contemporary Native American history. After high school, he went on to study architectural drafting at Bacone College, OK, and business at the University of San Francisco, CA. From 1968 to 1971, he worked for the National Indian Youth Council in Berkeley, CA. As a veteran of Indian activism from the ’60’s to the present, Sam English got involved in 1968 with Indian civil rights issues because of a desire to become more aware of Indian history. To cope with his outrage, he turned to alcohol.

“I had a lot of anger and hostility about the way we were treated as humans. And self-pity, that is what alcoholism is all about.” At the age of 39, and after 18 failed attempts at alcohol treatment facilities, he finally quit. “On December 10th, 1981, I drove my lance and decided I was not going to drink anymore.” From that moment forward, Sam English dedicated himself to using his art to document and serve his people. He became a well-known speaker and activist, owned and operated the Sam English Studio/Gallery, Ltd. in Old Town, Albuquerque. He continues to practice his art and pass on his spiritual journey of sobriety healing throughout the U.S. His “Healing Through the Arts” workshops in Palm Springs and the Bay Area have become legendary in the indigenous community.

Tragically, Sam English’s work has remained largely unnoticed by the wider art historical community, though he has been commissioned by, and has generously donated to many Native and non-Native Institutions. Though, at a casual glance his imagery seems simple – his work has sometimes been dismissed as “poster art” or “neo-American Indian expressionism” — it follows in the long and honored tradition of Native artists Allan Houser, Fritz Scholder, Kevin Red Star, T.C. Cannon, and Oscar Howe, and fits within the artistic framework of his fellow Anishinaabe artists, Norval Morrisseau, George Morrison, Patrick DesJarlait, Carl Gawboy, Melvin Losh, Dewey Goodwin, David Bradley and Jim Denomie. Sam’s images have been described by a Red Lake Midewiwin (Grand Medicine Lodge) member as “Ga-kina-nee-ja-ni-shi-na-baig”, All My People. They represent survival in a world of historic and intergenerational trauma; respect for ancestors and elders who have labored and battled against genocide, racism, oppression, marginalization, assimilation, and crushing imperialism; respect and adoration for a culture mindful of its cosmic, spiritual, hereditary, and environmental relationship to all things; respect and confidence in the healing power of artistic expression; and respect and hopefulness in the Native youth of America.

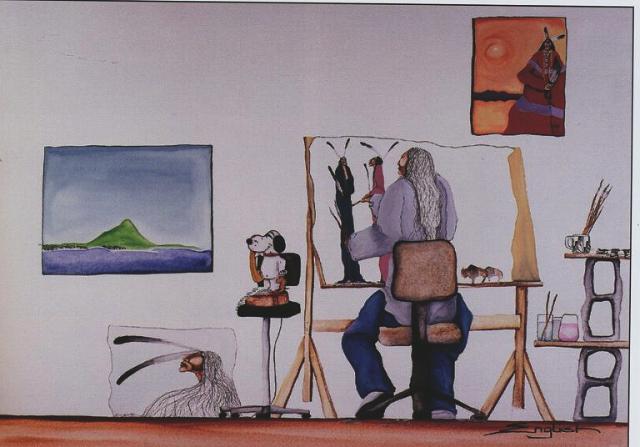

Underlying all of Sam’s aesthetic philosophy is “We” — a perpetual reference to his work as a spiritual gift and collaboration from (and with) the Creator. As Sam explains, “art is a spiritual process and when I talk about my art I include the Creator. Without the art, if I hadn’t continued to paint in my sobriety I wouldn’t be here painting. I wouldn’t be here, period. . . it doesn’t imply that I’m some sort of creative genius. I paint, but I think that I’m inspired to do this. I think somebody saved my life to do this. I think history, some contemporary history, and we try to do that with great dignity and humor and tradition and spirit.” One of the hallmarks of Sam’s work is elongated figures. One night in San Francisco, Sam says, “I was doing a city scene. . . and then, all of a sudden, there appeared a face at the top of a tall building and some eagle feathers and I thought, ‘hmm, I should convert these to long Indians… and as they were long and tall, elongated, I began to feel that they represented the pride and integrity of American Indian people to stand tall… I want my people looking up like they have a future, like they have life.”

His paintings are also characterized by their remarkable use of negative space. Figures and forms are not defined by black line. They float and transition from background to foreground as if they are traversing from the seen to the unseen world. It’s another unique technique that Sam utilizes to acknowledge the omnipotent influence of ancient ancestors and the way the spiritual and physical world are intertwined. With flowing hair, cloth, and limbs his figures seem to be floating in space. They speak of and transport the viewer to another dimension. At present, Sam is living in a hotel in Albuquerque, struggling with health issues, depression, and economic uncertainty. A few miles away, his original paintings. prints and books lie unnoticed in this storage unit, patiently waiting for an appropriate home. It is his hope that his life work will find that home—somewhere, somehow—in a Native American community or art institution that understands and values the work he has done over the past 50 years. In this way, he will be able to pass along the gift that the Creator gave him and that he hopes to share with the children and future generations. VIDEO COLORES: For All My Relations Sam English New Mexico PBS. Sam English on FaceBook: https://www.facebook.com/sam.english.7737769 Contributor Tom Kanthak is one of the founding members of the faculty and former Liaison for Indigenous Arts Education at the Minnesota Center for Arts Education in Minneapolis, MN. He is a practicing musician and artist who has been involved with the arts community of the Twin Cities since the late ’60’s. Weekly phone calls to Sam English are vital to his health and artistry. |

|||||||||||

|

|

|

|

||

|

|

||

| Canku Ota is a free Newsletter celebrating Native America, its traditions and accomplishments . We do not provide subscriber or visitor names to anyone. Some articles presented in Canku Ota may contain copyright material. We have received appropriate permissions for republishing any articles. Material appearing here is distributed without profit or monetary gain to those who have expressed an interest. This is in accordance with Title 17 U.S.C. Section 107. | ||

|

Canku Ota is a copyright ©

2000 - 2017 of Vicki Williams Barry and Paul Barry.

|

||

|

|

|

|

The "Canku

Ota - A Newsletter Celebrating Native America" web site and

its design is the

|

||

|

Copyright ©

1999 - 2017 of Paul C. Barry.

|

||

|

All Rights Reserved.

|

||