|

Canku Ota

|

|

|

(Many Paths)

|

||

|

An Online Newsletter

Celebrating Native America

|

||

|

October 2018 - Volume

16 Number 10

|

||

|

|

||

|

Look Who's Laughing

Now; The 50 Years Of Diné College

|

||

|

by Jourdan Bennett-Begaye

- Indian Country Today

|

||

Diné College, known as Navajo Community College before 1997, is the first and largest tribal college in the country Radio announcer Raymond Nakai hosted a popular radio show in the 1950s. "Navajos need their own college," he once said. Then a few years later he was elected chairman of the Navajo Nation and worked to make it so. He met with business leaders and Bureau of Indian Affairs officials in Window Rock, Arizona, and shared his goal of starting a college on the Navajo Nation. The chairman was laughed at. One BIA official said: "You think you Navajos could run a college?" Nakai replied, "I'm not asking for permission. I'm telling you what we're going to do," and he walked out of the room. "And here we are 50 years later," said Diné College President Charles "Monty" Roessel. "Look who's laughing now." Diné College, known as Navajo Community College before 1997, stands as the first and largest tribal college in the country with 6,532 alumni to date. The school was established in 1968 during the height of Vietnam War. Navajo leaders didn't want Navajo soldiers to leave again for college when they have just returned home from war. Diné College was that "higher education institution of the Navajo people, for the Navajo people by Navajo people," said Roessel, whose dad, Robert Roessel, was the first president of the college and his mom, Ruth Roessel, helped with the founding of the school. "There was a certain mentality that Navajo people deserved to be in a classroom." Nakai and Robert Roessel advocated frequently for self-determination for the Navajo Nation. This was a step in that direction. The college was launched a century after the Navajo Treaty of 1868, a treaty between the Navajo and the United States after thousands of tribal citizens were removed from their homelands and marched by the military some 400 miles to Fort Sumner, New Mexico.

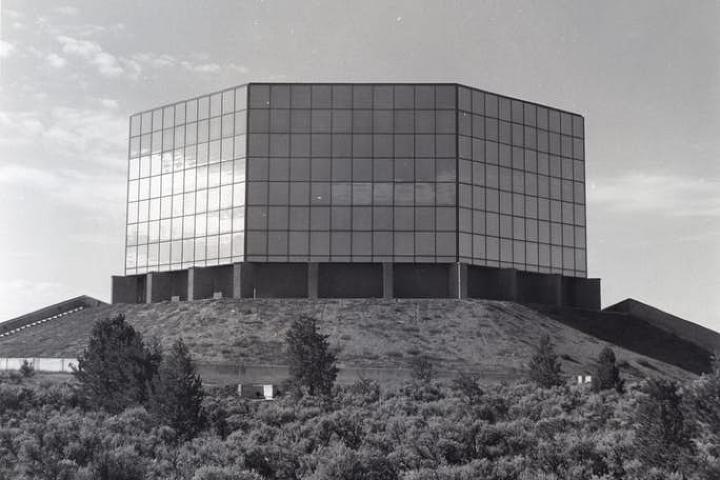

Growth of the college The college started out by sharing facilities with a high school, the BIA boarding school in Many Farms, Arizona. Classes started in the spring of 1969 with 301 students. Peter Iverson, a former history instructor at the college, reflected on his first teaching job at the college in an essay for the Journal of American Indian Education. He said the college needed someone quick, someone "young and foolish" to teach history since the last instructor backed out. He said, "Sure. I'll come to Many Farms," and packed his bags in Madison, Wisconsin. Students lived in Dormitory Nine if they didn't live near Many Farms or Chinle. Married couples lived in trailers and other students lived with relatives closeby. Three dorm residents shared a room with bunk beds with no rugs or carpet and harsh lighting. Windows couldn't open and students suffered the heat. "Some genius back in Washington, D.C. had determined that the altitude of Many Farms made air conditioning unnecessary," he wrote. The library wasn't full of studious students but would later come with high-class book collections. Some classes were taught in mobile homes. Students questioned if they were even attending a "real" college. The school had a men's basketball team full of talent but fan support decreased due to the department recruiting more non-Navajo players, primarily African-Americans. The program was canceled. Intercollegiate rodeo did well and still exists today. Along with rodeo, archery, men's cross country and women's cross country make up the athletic department. Students fought through the isolation of the campus with a local Bible radio station, fighting with the television to get a decent signal, homework (if they didn't copy one another's), or family responsibilities. Despite the lack of communication, students kept up with the news at that time, such as the Vietnam war and the Occupation of Alcatraz Island by Indians. Navajo leaders continued to fight for federal funding and finally received it in 1971 with the Navajo Community College Act. It gave "grants to the tribe for the construction, maintenance and operation of Navajo Community College and that it be designed and operated by the Navajo tribe to ensure that qualified Navajo and other applicants have educational opportunities." In 1973, the college moved to its new and central campus in Tsaile, Arizona about 40 minutes from Many Farms. After that, the college expanded to five other campuses in Arizona and New Mexico. Iverson mentions the uniqueness of courses offered at the college like Indian affairs, Indian economic development, urban Indians, Indian-white relations, and Indian law and government. Reputable speakers like Vine Deloria, Jr. were invited for talks. One of the difficulties of that Iverson wrote about was the teaching experience of white faculty. They couldn't replicate a standard college course. Non-Navajo faculty had to use inquiry circles and be the guide for students like independent study when learning about Indian literature, theory and psychology in coaching, Renaissance painting, and American drama.When Dr. Ned Hatathli, the college president from 1969 to 1972, was asked what is the difference between a regular college and a tribal college, he said, "For one thing, we don't teach that Columbus discovered America." Another president, Donald A. McCabe, said the school was a disaster because of the low standards. Students had to take three credit hours of Navajo language and six credit hours of of Navajo history. Math, social studies and science were not required. Graduates left with 64 credit hours but other schools didn't accept the credits. Now, the college continues to grow and the standards are higher. Iverson, who taught at the college from 1969 to 1972, said even though there's no one at the college who was part of the starting stages in Many Farms "the initial hopes and dreams of the college remain important and the institution's first years are instructive" and "tells us something about the enormous achievements in Indian education … also something about the distance that remains to be traveled."

There are currently 1,535 students enrolled across the six campuses and 62 faculty members total with 56.5 percent of those being Navajo with more faculty being added this fall. As an accredited collegiate institution, students can obtain an associate's and bachelor's degrees and certificates in 16 subject areas and 20 specialties. Students also have the option to complete their coursework online for certain programs. Earlier this month, Diné College received the green light to offer a bachelor's degree in Diné Studies as well as the approval to move forward in establishing a law school. Along with western philosophy, the institution uses the Diné traditional living system as the educational philosophy with a huge focus on their language, culture and history. Roessel said Diné College is not based on the outside perspective, or the glory of the United States. "This is a different story." It is about two stories: the one we're used to telling and the one we want to tell. "We have an opportunity," he said. "We don't live in two worlds, we live in a blended world. We're trying hard to prepare our students for that."

"My grandchild, education is the ladder." Navajos often refer to Chief Manuelito's quote when talking about education because he knew education was the only way Navajos could be independent. "My grandchild, education is the ladder. Tell our people to take it," he said. Diné College was Felisha Adams' top-choice school because of its history as the first tribal college and she wanted to be party of their tribal economic development program. A program not offered anywhere else in the country. Adams, Diné, could've gone in San Diego but she wanted to be on the Navajo reservation where you have the culture, language and history part of the faculty. "I wasn't getting the language exposure I was longing for in San Diego," she said. "I stuck to YouTube videos and old books. I didn't have anyone to speak in the language to." Learning the language helped her as president of the Associated Students of Diné College last year because the position also makes you a student representative on the Board of Regents, the guide for the college's future when it comes to goals and future programs. "Our board meetings had a lot of language embedded it," she said and asked Adams graduated in May with her bachelor's degree in business administration and started at the University of New Mexico's School of Law in Albuquerque. Just like Adams', Aaron Lee improved his Navajo language fluency and gained more knowledge about the culture. In fact, he said, "I know more Navajo now than I ever had." One memory that stands out to Lee is of him attending a ceremony. He introduced himself as student at Diné College and the person said, "You can't learn Navajo culture in a classroom. You have to learn it from your household." Lee agreed to disagree. "I left Diné College with more confidence than I ever had as a person overall. Not just knowing that I have a degree but with the knowledge of Navajo culture I have now and that I share with my nieces, nephews, and kids," he said. "That's what we talk about as Navajo people. It's what we keeping telling each other." The 32-year-old remembers his arm hurting from raising his hand so many times in class. He annoyed his professors with questions because he wanted to know the history, stories and songs. He hopes to be a sports psychologist one day using his associates degree in social and behavioral science and, soon, his bachelor's degree in psychology from Diné College. Dreams like Lee's started when he stumbled onto the college's campus and surprised by the affordable tuition rates, one of the many deciding factors for Native American and Alaskan Native students.

Trailblazer Diné College serves as the "role model" for the 38 tribal colleges and universities today. It is the only tribal college with its own bill, the Navajo Community College Act. Other institutions fall under the Tribally Controlled Community College Assistance Act of 1978 signed by President Jimmy Carter. In 1973, the first six tribally-controlled colleges established the American Indian Higher Education Consortium. The organization served as an advocate for American Indian education on Capitol Hill. President Lionel Bordeaux of Sinte Gleska University talked about his struggle for funding for the university with Dr. Roessel. It took the university six years to secure funding. "One time, a U.S. congressional representative told us that our pursuit of tribal colleges was to be respected but that it was wrong. He said, 'You Indians are good with your hands, stick to the arts and crafts. If you really want to do something meaningful, flood your reservations with chicken coops and hog pens. That's your future!'', he said to the Tribal Business Journal. "Another powerful lawmaker called our TCU bill the worst piece of legislation to ever cross his desk." Despite the push back from congressional leaders, Bordeaux said this educational and self-determination movement is needed all thanks to Diné College. "We can utilize this model to address and strengthen our peoples' lives as they prepare and begin a journey that enables future Native youth to realize their dreams and aspirations." The college is hosting their student scholarship gala on Sept. 22 in Scottsdale, Arizona with Mark Trahant, editor of Indian Country Today, as the master of ceremonies. Jourdan Bennett-Begaye, Diné, is a reporter/producer for Indian Country Today in Washington, D.C. Follow her on Twitter @jourdanbb. Email: jbennett-begaye@indiancountrytoday.com |

||||||||||

|

|

||

|

|

||

| Canku Ota is a free Newsletter celebrating Native America, its traditions and accomplishments . We do not provide subscriber or visitor names to anyone. Some articles presented in Canku Ota may contain copyright material. We have received appropriate permissions for republishing any articles. Material appearing here is distributed without profit or monetary gain to those who have expressed an interest. This is in accordance with Title 17 U.S.C. Section 107. | ||

|

Canku Ota is a copyright ©

2000 - 2018 of Vicki Williams Barry and Paul Barry.

|

||

|

|

|

|

The "Canku

Ota - A Newsletter Celebrating Native America" web site and

its design is the

|

||

|

Copyright ©

1999 - 2018 of Paul C. Barry.

|

||

|

All Rights Reserved.

|

||