|

Canku Ota

|

|

|

(Many Paths)

|

||

|

An Online Newsletter

Celebrating Native America

|

||

|

October 2018 - Volume

16 Number 10

|

||

|

|

||

|

Kyrie Irving's Roots

In The Standing Rock Sioux Tribe, And His Winding Journey Back

|

||

|

by Tim Bontemps - The

Washington Post

|

||

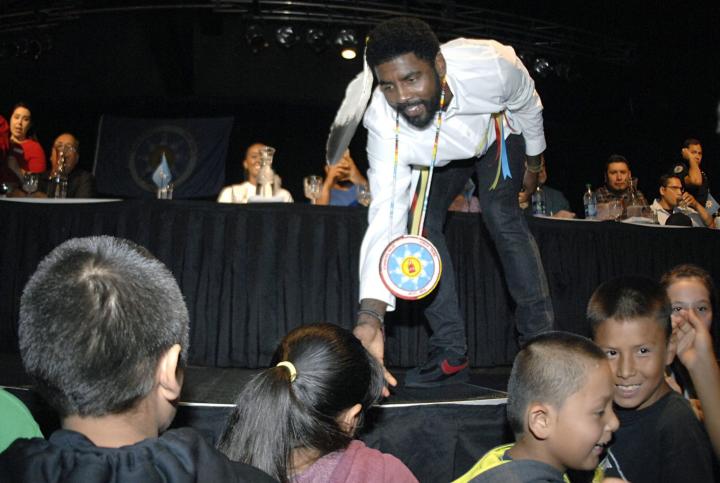

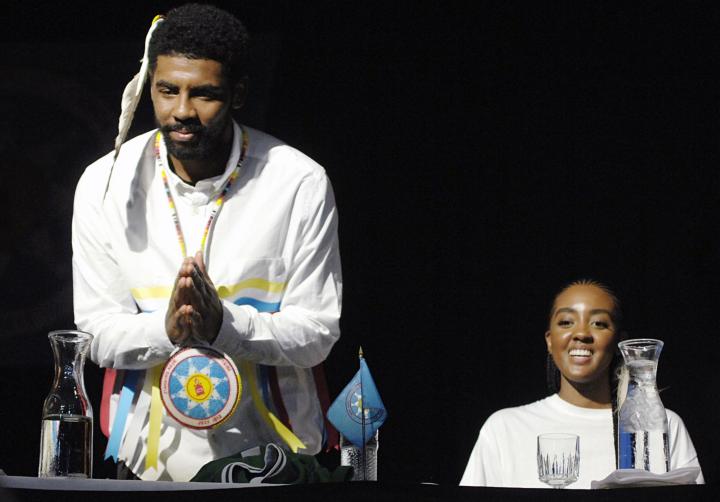

Cannon Ball, ND — Elizabeth Ann Larson Irving lies under a small patch of ground in the far corner of a tiny cemetery, tucked next to a pair of babies' graves from pioneer days. If not for a modest sign, and a tiny fence circling it, Rock Creek Cemetery wouldn't even be noticeable from the dirt road a few feet away. In 1996, Irving was buried here, less than 10 miles outside of Mitchell, S.D., where she spent eight of her 29 years, the adopted daughter of George and Norma Larson. Elizabeth, whose birth mother was Standing Rock Sioux Tribe, moved with her adopted family near Tacoma, Wash., became a star athlete in high school and met her husband at Boston University. The couple had two children together: a girl, Asia, and a boy, Kyrie. On Thursday, some 300 miles northwest of his mother's grave, the Boston Celtics star guard and his older sister were honored by the tribe of his mother's biological roots with a traditional Lakota naming ceremony in a day-long celebration held here at the Prairie Knights Pavilion. The ritual, which included Irving and his sister being presided over by a Lakota spiritual leader, Vernon Iron Cloud, saw them granted with the names "Little Mountain" and "Buffalo Woman," in what was just part of a celebration of their arrival. "I thank you guys from the bottom of my heart," Irving said in a speech at the end of the day's events. "I cannot wait to come back. "This is family for me now. I don't know anything else." The NBA is an international league, with players hailing from an array of backgrounds, but Irving's presence here Thursday showed how unusual his is. Two years ago, no one outside of his immediate family knew this possibility existed. Then he tweeted about the Dakota Pipeline, beginning a series of events that included him creating a shoe this year that incorporated the Standing Rock logo and culminated with him standing on a stage in front of roughly 1,000 people, including more than a hundred relatives he had never met.

'Wonderful,

rich heritage' In early August 1967, George and Norma Larson were Lutheran seminarians living in a little apartment above Carlson Funeral Home, which they cleaned at night. They lived there with their son, Steven, but were awaiting the arrival of an adopted daughter, whom the adoption agency had told them would be of Native American and black heritage. "We asked for a child who under the current conditions at the time would be most likely to go from foster care to foster care to foster care and not have a forever home," George Larson said. As they awaited their daughter's arrival, Norma was on a bus headed to her job as the church secretary at St. Anthony United Methodist Church when a woman caught her eye. "I saw this beautiful young woman, with hair all the way down her back," Norma said. "She was clearly Native American, and clearly very pregnant." Soon, the woman got off at a stop near the Booth Home, a place where unwed mothers received medical care and gave birth. "When we got Elizabeth," Norma said, "[I knew] that was her mother." If that was the case, it was the closest the Larsons ever came to meeting Meredith Marie Mountain. Elizabeth — named Cynthia Jeannette Mountain by her birth mother — was born Aug. 13, 1967 and was adopted nine days later by the Larsons. She spent eight childhood years in Mitchell, where George was the pastor at First Lutheran Church, before he moved his family to Puyallup, Wash., a suburb of Tacoma, to start Celebration Lutheran Church. A young girl of mixed descent raised by a white family in predominantly white towns, she struggled with her identity. George Larson remembered, while in Mitchell, watching Elizabeth walk home from school one day in second grade, as kids followed behind calling her the N-word repeatedly. Despite some prodding by her parents as a teenager, though, Elizabeth never was interested in exploring her roots. "We really wanted her to realize that she has this wonderful, rich heritage that goes back thousands of years," George Larson said, "[with] rich traditions and lots of wisdom." A star athlete in high school, Elizabeth attended Boston University and played volleyball. There she met Drederick Irving, the star of the men's basketball team. The couple would later marry and have Asia and Kyrie. Meantime, Elizabeth's biological mom, Meredith Marie Mountain, had gone on to marry and have two more daughters: Elizabeth, who shared a name with the half-sister she never met, and Kelly. "My mom told me at the age of 13 that she had had a child prior to my sister and I and that she had put her up for adoption," Kelly Brinkley said. "That was, however, many years ago, so it wasn't something easy to start looking for or pursuing her. She told us, and that was pretty much it." Eventually, Elizabeth did attempt to contact her Indian family, but after initial dialogue, she pulled back. Meredith Marie Mountain died in 1995, and Elizabeth Irving died the next year at age 29, after contracting sepsis during a hospital stay. Kyrie was 4 years old. Elizabeth's story remained undiscovered until a tweet changed everything. 'A home connection' Kyrie Irving's first public acknowledgment of his past came on Nov. 22, 2016, two days before Thanksgiving, when he tweeted his support for those protesting the Keystone Pipeline at Standing Rock: "My prayers and thoughts are with everyone protesting at Standing Rock, I am with you all. #NoDAPL Defend the Sacred." That same week, George and Norma Larson had brought their daughter's things to Irving's house in Cleveland for their grandchildren to sift through. For Irving and his sister, it was a chance to grow closer to their mother. Then, a few months later, Irving went further in an interview with ESPN. "I'm actually Sioux Indian," Irving said. "My mom was adopted .?.?. there's a home connection that was going on there." By then, Brinkley knew the basketball star was her nephew. In 2006, she had received paperwork stating that both Asia and Kyrie were eligible for Indian land grant rights and that she was the guardian of those rights. But she never reached out. At first she was unsure of how they'd respond, given their mother's reticence before she died. Then, as Kyrie's star rose, she didn't want to seem like she was chasing fame. But for Char White Mountain, Meredith Marie's niece, Irving's public pronouncements meant something else: a chance to reunite her aunt's family. The only problem: She and her family didn't have the faintest idea of how to contact him.

So, they improvised. They wrote the Maury Povich show in hopes of staging a reunion but didn't hear back. They called Nike, telling their story to a sales rep after buying pairs of his shoes; an operator politely listened then hung up. They even briefly considered holding up a banner at game in the hopes of attracting Kyrie's attention. Eventually, Danielle Finn, named the tribe's external affairs director in April, emailed Irving's agency and established a dialogue. After months of back-and-forth, Thursday's ceremony was scheduled. "It's something I've been searching for," Char White Mountain said. "Our prayers were answered." The event was captivating and emotional. Near its conclusion, Asia Irving appeared to wipe away tears. Kyrie stood next to her with his head down and eyes closed. George and Norma Larson stood alongside their grandchildren, watching their daughter's family ties come together. Brinkley finally got the chance to connect with the niece and nephew she has known of for more than a decade but never met. For the tribe, not only was it a chance to welcome in Kyrie and Asia Irving but also to send a message to other adopted children. "This is an opportunity to let other children of Native American heritage to come home to their people," said Frank Jamerson, a former tribal councilman. "We never forget our loved ones .?.?. so for those individuals that may know their family was displaced by adoption, find your loved ones and bring them home." More than 50 years after that fateful day when one mother crossed paths with another on a bus in Saint Paul, the two strands of Elizabeth Irving's story were woven back together. In doing so, they created new bonds. "It's a day for closure," George Larson said. |

||||||

|

|

|

|

||

|

|

||

| Canku Ota is a free Newsletter celebrating Native America, its traditions and accomplishments . We do not provide subscriber or visitor names to anyone. Some articles presented in Canku Ota may contain copyright material. We have received appropriate permissions for republishing any articles. Material appearing here is distributed without profit or monetary gain to those who have expressed an interest. This is in accordance with Title 17 U.S.C. Section 107. | ||

|

Canku Ota is a copyright ©

2000 - 2018 of Vicki Williams Barry and Paul Barry.

|

||

|

|

|

|

The "Canku

Ota - A Newsletter Celebrating Native America" web site and

its design is the

|

||

|

Copyright ©

1999 - 2018 of Paul C. Barry.

|

||

|

All Rights Reserved.

|

||