|

Canku Ota

|

|

|

(Many Paths)

|

||

|

An Online Newsletter

Celebrating Native America

|

||

|

OCTOBER 2020 - Volume

18 Number 10

|

||

|

|

||

|

The Case For Dinétah

|

||

|

by Mark Trahant - Indian

Country Today

|

||

Statehood will not fix the problems facing the Navajo Nation but it would do two things: Add a voice in Congress and get more money from Washington This is a moment of dramatic change. The upside of a year like 2020 is that notions once thought impossible are being debated anew. Recently Senate Minority Leader Chuck Schumer, a Democrat from New York, told MSNBC that he’d “love to make” both Washington, D.C., and Puerto Rico states. The Democrats’ presidential nominee, Joe Biden, has also called for the island and its 3.5 million American citizens to get statehood. The question will be voted on next month, when Puerto Ricans will decide between statehood, territorial status, or something else. Though additional hurdles would still remain, Democrats have indicated there will be action on statehood should they win the election, and especially if they sweep the House, Senate and White House. But is that all? Is this also the moment for Congress to consider the Navajo Nation for statehood? The idea of a state of Navajo, or state of Dinétah, has surfaced from time to time. The concept of an Indigenous state has a rich history in the United States as well as around the world. (A note about language: The word Dinétah, or “among the people,” is used in this piece; however, should statehood proceed, Navajo citizens would make the call on a name.) Nathan Lefthand wrote about statehood in an Indian Country Today op-ed in 2013. “The State of Navajo. It’s almost Zen, how it rolls off the tongue,” he wrote. “This idea has been deep in the reptilian core of my brain for some time, lying dormant till news of the Navajo government was finalizing its Medicaid feasibility study to go before Congress for approval this spring, thanks to the Affordable Care Act. Then boom, all those thoughts and ideas to somehow fix or feed the many problems we have.” Statehood will not fix the problems facing the Navajo Nation, but it would do two things: Add representation in Congress and open up more funding. The federal government has a different formula for how to distribute money to states than it does for tribal governments. So much so that federal dollars are the single largest share of every state budget, averaging about a third of all the money coming in. Nearly $1 of every $5 spent by Congress is shipped to states. And some states do better than others. New Mexico is at the top of the list. The Brookings Institute estimates the “transfer of payments” between the federal government and that state at more than $3,500 per person. If the same formula is applied to the Navajo Nation, the total would be around $600 million per year. As a comparison, emergency funding for the tribe in the Coronavirus Aid, Relief and Economic Security Act was $714 million. But that was a one-time funding source (and the most ever spent on Indian Country). There is no guarantee the state of Dinétah would receive that much. But even if the state with the lowest percentage of federal transfers is used, that base number would still exceed $340 million a year. (Then, so much of federal spending is based on Census data, including poverty levels. So a state of Dinétah is likely to be on the higher side of that equation).

Statehood 101 The process for a state to be created out of another state, under the Constitution, is for Congress to act, followed by action from each of the state legislatures. In this case, that would be Arizona, New Mexico and Utah. Article IV, Section 3 outlines this process. “New States may be admitted by the Congress into this Union; but no new States shall be formed or erected within the Jurisdiction of any other State; nor any State be formed by the Junction of two or more States, or parts of States, without the Consent of the Legislatures of the States concerned as well as of the Congress.”

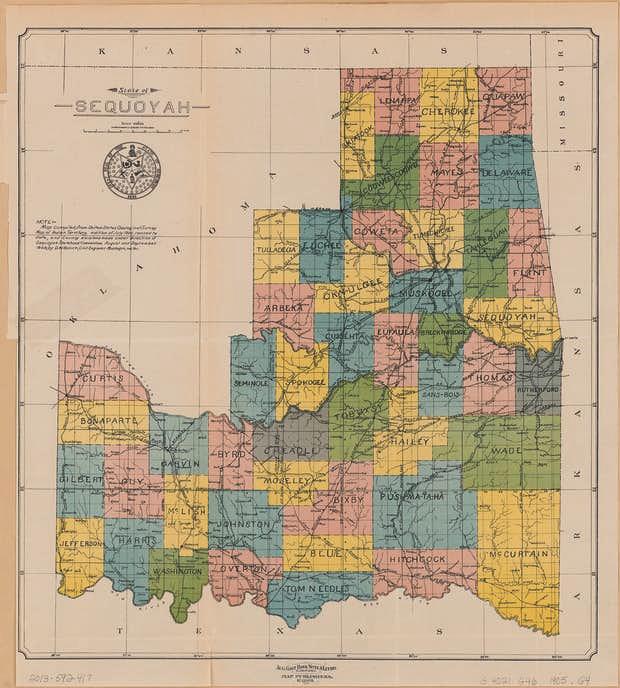

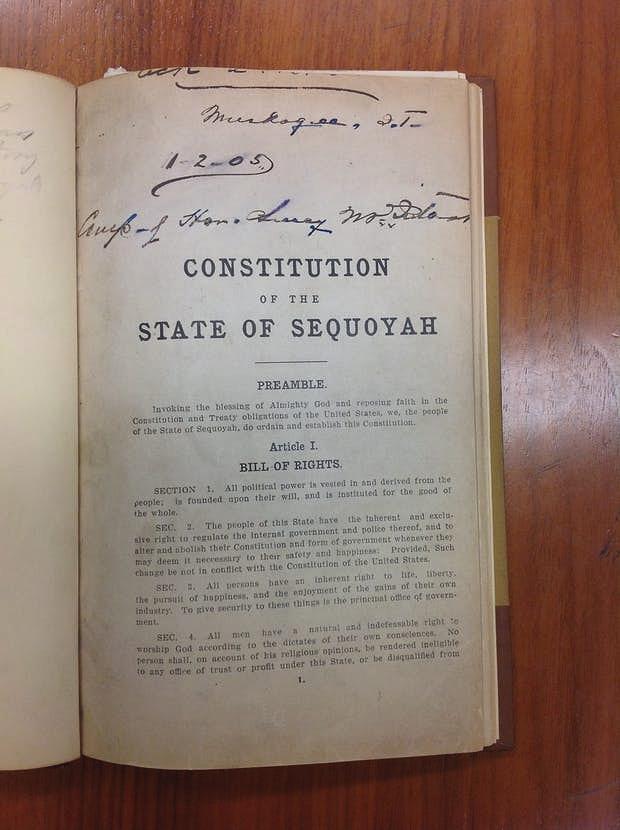

But there is another view. Some argue Congress could act unilaterally because the Navajo Nation’s 1868 treaty predates the creation of Arizona and New Mexico in 1912 and Utah in 1896. The idea of an Indigenous state has been tried before. Five tribes in Oklahoma held a convention to form the state of Sequoyah out of what was then the Indian Territory. “Their goal: to create a state government that might replace tribal sovereignty with a rough second best — Indian sovereignty through democratic majority,” according to the Library of Congress. “Their efforts yielded a constitution, which included a bill of rights, provisions for the separation of powers among three branches of government, the establishment of counties and their borders, the regulation of trade, and the prohibition of the manufacture of intoxicating spirits, among other things.” Voters in the territory, both Native and White, overwhelmingly agreed. But a Republican-led Congress wasn’t about to allow two states to be formed that would send Democrats to Washington. And, as a recent National Geographic article pointed out, many lawmakers disliked the idea of a state governed by Native leaders instead of one by and for White citizens. “Instead, Congress passed the Oklahoma Enabling Act of 1906. This new law settled the debate over statehood by inviting representatives to write a state constitution, choose a capital, and move forward with a state that combined both Oklahoma and Indian Territories.” Every state sends at least one representative to the U.S. House and two members to the U.S. Senate.

Indigenous sovereignty More recent examples of the Indigenous state can be found in Greenland and Canada’s Nunavut. Nunavut is a self-governing territory created in 1999 and home to some 40,000 people, mostly Inuit. Inuit is the Inuktitut word for “people”; Inuk for “person.” And Nunavut is an Inuktitut word for “our land.” A 1998 paper from the University of Queensland’s Centre for Democracy compared the importance of Nunavut to creating a stronger governance system for Aboriginal communities in the Torres Strait. "Both are cultures so different from the traditions of the country's majority that little real national understanding or appreciation of them exists. Both draw strength and inspiration from ethnic kin across international borders, some of whom are self-governing. Both are politically marginal, even in comparison with other indigenous people in the country,” the paper said. “Both feel threatened by growing resource extraction and related pollution and shipment in their homelands.”

Self-government was seen as a key element in national sovereignty. “Not only did the Federal Government of Canada concede the right of the Inuit of Nunavut to cultural self-preservation, self-determination and self-rule within a framework for Inuit- dominated public government under the sovereignty of the Canadian Federal Government, it also agreed to most of the expense,” wrote Holly Dobbins in her 2019 doctoral thesis at Syracuse University. She described the process as one of “negotiation and community consultation.” Aluki Kotierk, Inuit, is president of Nunavut Tunnnavik Incorporated, an Inuit organization that ensures promises made under the Nunavut Agreement are carried out. She wrote in Policy Options about one promise that has fallen short: “With the creation of Nunavut, Canada missed a bold, nation-building opportunity. Canada could have recognized Inuktut as the founding language of Nunavut. Canada could have sufficiently funded and supported Inuktut so that it would be the working language of the territorial government. Inuktut as the language of government was costed out, but the Government of Canada’s Department of Finance decided to postpone funding it to a later date. That date has yet to come.” She said the language challenge is daunting. “Inuktut use in Nunavut is declining by 1 percent per year,” she wrote. “At this rate by 2050 only 4 percent of us will be speaking Inuktut at home.” Another Inuit homeland, Greenland, or Naalakkersuisut, also has home rule but remains part of colonial Denmark. For now. Full international independence could come as soon as next year because under Danish law, a referendum on independence could happen at any time. President Donald Trump said in August 2019 that he’d like to buy Greenland from Denmark, ignoring the island’s self rule. The country’s leader, speaking in Greenlandic, told the Arctic Circle conference last year that Greenland is “not for sale,” and the country “cannot be valued with money.”

Tribal sovereignty, state sovereignty “I strongly believe that Indian Country must make its move to capitalize on tribal sovereignty and establish a more firm and stable identity,” said Lawrence Isaac Jr., dean of the Diné College School of Diné Studies & Education. “Navajo Nation is slowly deteriorating in a number of key attributes beginning with its language; cultural core values; and unique identity. … Indian Country must do better in terms of governmental representation and ownership as original inhabitants.” He said the Navajo Nation should “carefully calculate” its next move toward “more authority and home rule if it's to survive in the next decades; it's that critical.” Charles Wilkinson is an emeritus professor at the University of Colorado Law School and the author of more than a dozen books on federal-Indian policy. “Right now, Navajo can probably be described as a federal government. The Navajo national government is overarching, like the United States. The chapters, which of course are unique, have many similarities to counties, so you have two levels of government. That structure could be incorporated into a statehood arrangement without losing the traditional, cultural and political relationship between the national Navajo government with headquarters in Window Rock and the chapters,” he wrote. This is essentially the case in Alaska, where more than 230 villages are recognized by the United States as tribal governments. The Navajo Nation has 110 chapters and five regions, or agencies, that could be incorporated into that kind of framework. Wilkinson said there are other problems with statehood. “First, now citizenship depends upon Navajo blood, and I don't think it would be politically possible, and probably constitutionally invalid, for that to continue. That means that residents of the geographical nation would have to have voting rights,” he wrote. “Over time, the number of non-Navajo residents could be significant. I think Nunavut has had difficulties with that.” Former Navajo Nation Attorney General Ethel Branch called the citizenship issue “interesting; super, super interesting.” What if the approach were along the lines of immigration? Then citizenship could be defined by attributes beyond birthright. “What do we want our citizenry to reflect?” she asked. “Culturally, linguistically or in terms of their knowledge and their political participation.” She said in a way that would echo Navajo history, where people could learn the language or the culture as an entry point. More than a century ago people became Navajo by learning language or culture. “Honestly, when I think about why we would want to have statehood, it's not just having a senator and representative in Congress,” she said. “It's also about having a direct flow of funds between the federal government and the Navajo Nation instead of having to go to the states and the counties.” And many of those counties are run largely by non-Indians. Statehood would change that. Branch said another significant change would be in the criminal justice system. As it stands, three states, the federal government and tribal systems all have different jurisdiction and authority on the Navajo Nation. Most of the time, she said, there is a good flow of information, but there are also cases missed. “Sometimes they wouldn't even tell us when a federal crime occurred on our land; we had to hear about it indirectly. And that's really problematic,” she said. Statehood could also mean a single U.S. attorney’s office and more shared standards that are common across states. But that’s not the big picture. “What do we care about more?” asks Branch. “Considering statehood is important so we can ensure an equitable allocation of resources. I was just looking at a recent HUD report and in the context of the voting rights issue, it is reported that anywhere from 40-some-odd thousand to 80-some-odd thousand Navajo tribal members are house surfing or essentially homeless at any given moment.” That means a quarter to a half of tribal members are homeless. “When you have 27,000 square miles, I just feel like that's criminal. No one on the Navajo Nation should be homeless, and maybe moving to that statehood status” would open up new resources, possibilities and even access to more homes. It’s that question about resources — as well as representation — that makes the case for Dinétah. There are other options, of course. Congress could fund tribal nations with a formula that is similar to states. A fully funded Indian health system is an example of that; even if Medicaid and other third-party insurance funds are included, federal spending on health remains far below that of any other health system (including federal prisons). As Dr. Donald Warne of the University of North Dakota wrote in a paper for the National Institutes of Medicine: “To bring the IHS budget to an equitable level … would require approximately an additional $3 billion per year. With a Department of Health and Human Services budget of more than $800 billion per year, this increase represents only a few tenths of 1 percent, and this increase would have a significant return on investment in terms of saving lives and reducing human suffering.” The same idea of equity could apply across the board, from highways to higher education. There is also the question of representation. The territories of the United States, such as Puerto Rico, Guam and the Commonwealth of the Northern Mariana Islands have marginal representation in Congress (a House delegate who can serve in committees but not vote). And even that is not equitable: Delegate Gregorio K. C. Sablan represents the Northern Mariana Islands with a constituency of about 55,000 people, less than a third of the Navajo Nation. A delegate in Congress does not go far enough for Branch. “I don't want the nonvoting,” she said. “I guess that's marginally helpful, but, you need someone who can introduce legislation and carry that to the finish line and including through their own votes.” |

|||||||||

|

|

|

|

||

|

|

||

| Canku Ota is a free Newsletter celebrating Native America, its traditions and accomplishments . We do not provide subscriber or visitor names to anyone. Some articles presented in Canku Ota may contain copyright material. We have received appropriate permissions for republishing any articles. Material appearing here is distributed without profit or monetary gain to those who have expressed an interest. This is in accordance with Title 17 U.S.C. Section 107. | ||

|

Canku Ota is a copyright ©

2000 - 2020 of Vicki Williams Barry and Paul Barry.

|

||

|

|

|

|

The "Canku

Ota - A Newsletter Celebrating Native America" web site and

its design is the

|

||

|

Copyright ©

1999 - 2020 of Paul C. Barry.

|

||

|

All Rights Reserved.

|

||