|

Canku Ota

|

|

|

(Many Paths)

|

||

|

An Online Newsletter

Celebrating Native America

|

||

|

December 2020 - Volume

18 Number 12

|

||

|

|

||

|

Tribal Territories

Have The Right To Protect Their People Against The Pandemic

|

||

|

by Sarah Stacke and

Magnum Foundation

|

||

|

South Dakota has

resisted shutting down in the face of Covid-19. The Cheyenne River

Reservation is taking matters into its own hands.

The ongoing struggle for racial justice. The future for immigrant families. The health and well-being of all Americans. The very fate of our fragile planet. The United States faces a crossroads in 2020. Seeking out the stories flying under the national radar, The Nation and Magnum Foundation are partnering on What's At Stake, a series of photo essays from across the country through the lenses of independent imagemakers. Follow the whole series here. This installment was produced with support from the Economic Hardship Reporting Project. CHEYENNE RIVER RESERVATION, SD—By the time I visited, the checkpoints were already a point of contention between the tribe and the state. As a sovereign Lakota nation, the Cheyenne River Reservation is entitled to control who enters its territory. When the coronavirus pandemic reached across the Great Plains earlier this year, it acted quickly. Since April, the tribal leadership of Cheyenne River has allowed only residents, essential workers, and commercial vehicles to enter the reservation. Set up on all roads with access to the reservation, the checkpoints were one of several actions taken by the tribe to prevent the spread of the virus and to protect their people, culture, and rights. But South Dakota Governor Kristi Noem—who has refused to enforce a mask mandate, restrict gatherings in bars, restaurants, and churches, or institute a stay-at-home order—ordered the barriers removed.

The tribe has so far rejected Noem's demand, and as I talked to friends and conducted interviews here in late October, what I heard over and over was the deeply rooted knowledge that the local, state, and federal governments are not going to help the tribe, and moreover, will support regulations that harm the people of Cheyenne River. The threat of the virus to an already high-risk population with an eight-bed hospital facility and roughly 12,000 residents was tremendous. To prepare, the tribe converted a college dormitory into a makeshift hospital with 30 beds. Then, the Bureau of Indian Affairs changed the locks and wouldn't hand over the keys. Tribal Chairman Harold Frazier said to me, "I told the BIA ever since you people killed Sitting Bull, your mission has been to control us and keep us down." Frazier believes the decision to change the locks goes all the way to Trump, via the desk of Noem. "Growing up, my teachings told me when there is sickness near you, be humble, try not to fight, be strong, say prayers, and be a good person," said Frazier. "History shows us that prayer will get us through. That's why it's important to keep our prayers strong."

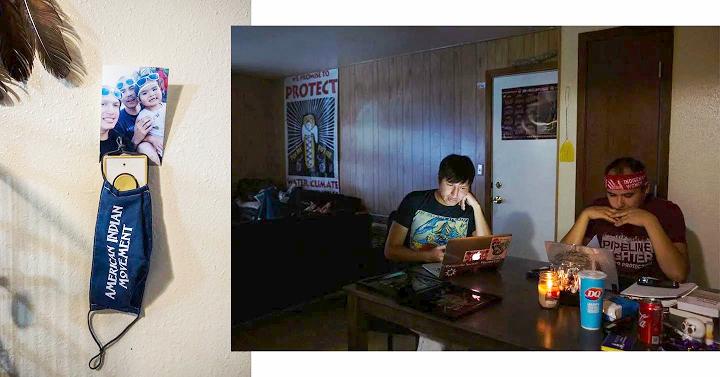

Compounding the difficulties for tribal leadership is the fact that many non-Native people own and live on land on the reservation, and many of them have been less likely to avoid travel, to wear masks, and in general follow health guidelines to prevent the spread of the virus. This wasn't my first trip to Cheyenne River. I met activists Danny Grassrope and Joseph White Eyes in 2016 during the uprising against the Dakota Access Pipeline near the Standing Rock Reservation. I've visited Grassrope and White Eyes many times in the years since. They've introduced me to their families and friends, and shared their lives with me. This story wouldn't have been possible without the doors they opened, their hospitality, and their trust. On this particular trip, White Eyes drove me to a remote checkpoint during a snowstorm—at night—then sat in the truck with me for over two hours while I scanned the darkness for headlights, waiting for cars to approach the barrier. Grassrope cooked dinners and together with White Eyes led me to Mona Grindstone, Tami Hale, and Joyce Edwards, three women who invited me into their homes and histories.

What struck me about Cheyenne River's response to the pandemic was that leaders recognized early on that they were responsible for the lives of the people, and they would do everything in their power to prevent unnecessary death. The Lakota people have dealt with novel viruses before. Upon the arrival of Europeans in the Americas, Native Americans suffered unimaginable levels of death from flu, smallpox, and measles. Since then, many Native American tribes have gone to extraordinary lengths to protect their people from disease. The message I received when talking to people here was clear: The tribe must protect itself at all costs, because no one else will.

Staffing the checkpoints is hard work. South Dakota's winters are brutal, and some drivers are angry that they can't access the reservation. Still, hundreds of people stepped forward to be deputized as special health and safety officers, and they have been running the checkpoints for over nine months. Remi Bald Eagle, the intergovernmental affairs coordinator for the tribe, told me, "?We have to do what we can with what we have. And what we have is strong, resilient and beautifully humorous people who are willing to lay down their lives and stand on our borders and stand outside quarantine homes and sit in our stores and do the work necessary to help keep this virus from spreading."

In the early months of the pandemic, even as South Dakota's Covid-19 caseload climbed, the virus didn't make significant inroads into the Cheyenne River Reservation. But in November, positive cases and deaths spiked on the reservation and the tribe enacted the highest level of its Covid-19 response plan. Two weeks ago, the seven-day test-positivity rate on the reservation climbed to 12.9 percent. Bald Eagle explained it to me this way: "?The tendrils of arrogance and egotism are still strapped to us from the American government. Non-tribal-members who live on the reservation feel like they shouldn't be subject to silly things like science or common sense. Non-members are not wearing masks. That's why we're getting the cases we're getting now."

The tribe's response to the pandemic, said community organizer Marcella Gilbert, "is more than an expression of sovereignty. It's a way of life and the future of our people. Our ancestors…gave their lives and their lifeways and their languages and their families and their children so we can at least say we have treaty obligations, we have water rights, we're a sovereign nation. This land holds everything that we are."

Sarah Stacke Sarah Stacke is a photographer and archive investigator and a co-founder of The 400 Years Project, a photography project looking at the evolution of Native American identity, rights, and representation, centering the Native voice. Follow Sarah on Instagram @sarah_stacke and @400yearsproject. Magnum Foundation Magnum Foundation is a nonprofit organization that expands creativity and diversity in documentary photography, activating new audiences and ideas through the innovative use of images.

Economic

Hardship Reporting Project (EHRP) THE

400 YEARS PROJECT MAGNUM

FOUNDATION |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

||

|

|

||

| Canku Ota is a free Newsletter celebrating Native America, its traditions and accomplishments . We do not provide subscriber or visitor names to anyone. Some articles presented in Canku Ota may contain copyright material. We have received appropriate permissions for republishing any articles. Material appearing here is distributed without profit or monetary gain to those who have expressed an interest. This is in accordance with Title 17 U.S.C. Section 107. | ||

|

Canku Ota is a copyright ©

2000 - 2020 of Vicki Williams Barry and Paul Barry.

|

||

|

|

|

|

The "Canku

Ota - A Newsletter Celebrating Native America" web site and

its design is the

|

||

|

Copyright ©

1999 - 2020 of Paul C. Barry.

|

||

|

All Rights Reserved.

|

||