|

Canku Ota

|

|

|

(Many Paths)

|

||

|

An Online Newsletter

Celebrating Native America

|

||

|

July 2021 - Volume 19

Number 7

|

||

|

|

||

|

How Indigenous Leaders

Are Pushing To Vaccinate Their Hard-Hit Communities

|

||

|

by Sarah Stacke, Brian

Adams, Russel Albery Daniels and Tahila Mintz - National Geeographic

|

||

|

Indigenous Americans

face higher mortality rates from COVID-19. How have tribal communities

responded to vaccination efforts?

When the COVID-19 pandemic reached the Great Plains in early 2020, the Cheyenne River Sioux Tribe set up checkpoints on all roads passing through the Cheyenne River reservation in a robust effort to protect tribal members. But over the past year, Indigenous leaders—from Alaska to Western New York—have made strides in vaccination rates. The pandemic has hit Indigenous communities disproportionately hard, compounded by generations of historical trauma and mistrust. According to an independent study done by the APM Research Lab published in March 2021, Indigenous Americans have the highest actual COVID-19 mortality rates nationwide, accounting for 256 per 100,000 deaths in the United States. Indigenous communities came to realize that the only way to beat the spread of infection was through community efforts, transparency, and access to the vaccine—and historic resilience. "We survived massacres, wars with the U.S., the laws the U.S. made against us. We survived prejudice, racism, genocide, sterilization, and boarding schools," says Remi Bald Eagle, Intergovernmental Affairs Coordinator for the Cheyenne River Sioux Tribe. "This is just another thing to survive." Here is how various tribes have responded to the vaccination effort.

Cheyenne River Sioux Tribe Like the rest of the U.S., the Cheyenne River Reservation, a sovereign Lakota nation located in South Dakota just south of Standing Rock, has reached a COVID-19 vaccination plateau in the wake of President Joe Biden's goal of ensuring vaccinations for 160 million Americans this summer. The prevailing cause of vaccine hesitancy among some Indigenous communities is lack of trust due to a troubling history. In the 1960s and '70s, the Indian Health Service, the same U.S. government agency now distributing a significant portion of the vaccine on the Cheyenne River Reservation, sterilized 25-40 percent of Native American women of childbearing age, against their knowledge or approval. "Mass sterilization to most people is just an event," Bald Eagle says. "But to us that's family that never made it here."

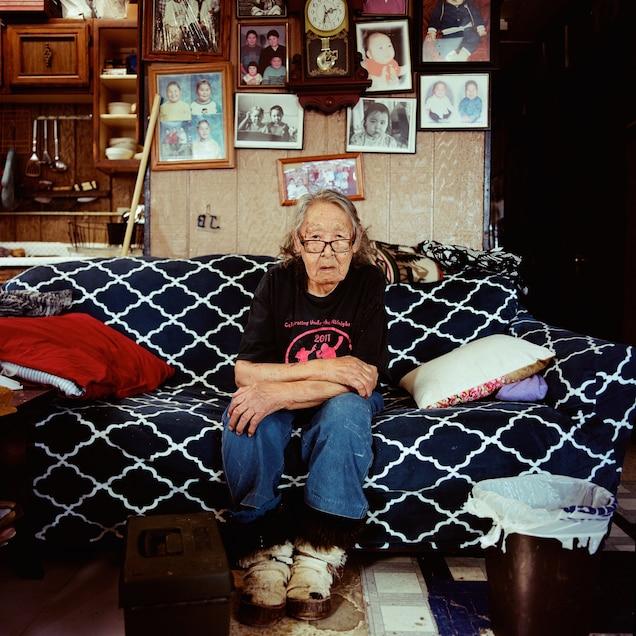

Access to the vaccine and reliable information about its effects have been key components to increasing the number of people opting to take the shot. Since the vaccine arrived in late 2020, CRST Tribal Health infection control nurse and tribal member Molly Longbrake has traveled thousands of miles to provide the vaccine to those living in the farthest reaches of the roughly 4,000-square-mile reservation. Along with her team, Longbrake has also made house calls and spent time on the phone offering information. "Education, education, education," is how she says the team address those who decline the shot, are on the fence, or ask for more information. "It's such a scary disease," says Longbrake, whose mother, Donna Rae Peterson, died from COVID-19. "Our main goal is to protect everybody." But even as she moves to get as many people vaccinated as possible, the lingering doubts about potential long-term effects remain cause for concern. Among the questions raised by tribal members: What's it going to do a year down the road? Ten years down the road? Will it cause infertility? Kivalina, Alaska In the small, traditional Iñupiat Eskimo village of Kivalina on the northwest coast of Alaska, roughly 40 percent of the 400 residents have been diagnosed with COVID-19. Yet, with this startling number, vaccination rates remain a challenge with only an estimated 21 percent of the people in the village having received shots. Although Alaska was one of the first states to make the vaccine available to the Indigenous population, the vaccine hesitancy reflects a community reeling from the aftereffects of a troubled history with the U.S. government and the inability to find places for COVID-19 positive cases to isolate outside their homes. Located on an eight-mile barrier island, Kivalina still struggles with the increased risk of widespread community transmission due to the village's remote location. Sitting just 80 miles above the Arctic Circle, vaccines are delivered by plane as they become available. Reba Adams, the assistant manager for a small grocery store called Kivalina Native, contracted COVID-19 during a large village outbreak that occurred in early January of 2021. This outbreak infected 44 people, roughly 10 percent of the entire village population. "I wouldn't know exactly where or how I got it because I work in a public place," says Adams. "My family who lives with us had it before me." Adams was ready to receive the vaccine, stating she only wants to keep her kids and family safe. "I have motivation to get vaccinated because of my job and family," she says. Elders in this community distrusted the speed at which the COVID-19 vaccine was approved for distribution, recalling the well-documented iodine experiment carried out by the U.S. Air Force in the 1950s. As many as 120 people—most of whom were Alaska Natives—were fed radioactive iodine to determine the drugs' effect on their thyroid glands. At the time, officials were acting on a belief that it might provide answers as to how Alaska natives could survive arctic winters. That history, coupled with today's quick vaccine response to the pandemic, gave Enoch Adams, Jr., a reverend at the Kivalina Episcopal Church, cause for concern. He and his family have opted not to receive the vaccine yet. "It takes years to develop a vaccine and this one was made in what, six months? There's too much uncertainty."

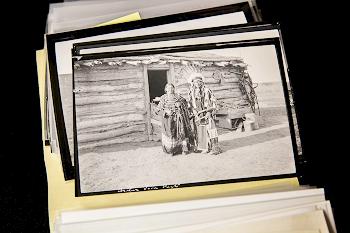

(Photograph by Brian Adams)

(Photograph by Brian Adams)

Northern Ute Reservation At the Northern Ute Reservation, in Utah, home to nearly 3,000 members of the Ute Tribe, the community united to protect their elders. Vaccine efforts were boosted by social media posts, family prayer, and traditional medicine, resulting in 95 percent of elders obtaining shots. "My main goal is to ease my people," says Henry Howell, a Northern Ute Sundance Chief. Along with his wife, Dondie, he worked nonstop gathering medicine and praying for their community while also maintaining their regular full-time jobs. "Many of our elders aged due to depression and fear. I visited and prayed with them three times a week." Howell said that the lockdown during the height of the pandemic can be compared to the beginning of reservation times when mandates and resolutions restricted traditional ceremonies. Families were encouraged to hold ceremonies and prayers at home.

(photograph by Russel Daniels)

On the Northern Ute reservation, Bear Dance gatherings usually begin in May. This social ceremony honors the waking of the bear, celebrates the coming-of-age for young people, and recharges the community—while ushering in Spring. This dance is medicine that Ute communities are eager to celebrate. As tribal members received their vaccines, they began to emerge from the mandated pandemic lockdown and fulfilled their desire to adorn themselves in traditional regalia. "We are a sharing tribe," says Felecia Pike-Cuch, manager of the Ute Tribe Emergency Management team based at Fort Duchesne, Utah, on the Northern Ute Reservation. "The EM team stepped up to help assist and protect this tight-knit community; secured early COVID tests; organized and delivered supplies; sanitized tribal offices, homes, and schools; secured vaccines; and set up a public vaccination clinic in conjunction with Indian Health Services." Currently, vaccines are offered to anybody within eastern Utah Tri-Counties. Seneca Nation In New York, the Seneca Nation of Indians is contending with vaccine hesitation issues as the rollout slowly continues to reach its saturation point. Jade Maybee, who lives with her husband Brett and their two sons, became a nurse more than three years ago at the Olean General Hospital, and worked in the ward designated for treating COVID-19 patients. "We had a very high period of cases in December 2020 into January 2021, where we typically have our flu season," says Jade Maybee. "And with COVID-19 there were a lot of people that had died, and it was around that time they started to push out vaccines to our community, starting with healthcare workers."

This push in vaccines helped to reduce the number of COVID-19 patients seen in her hospital, but Jade still worries about the unpredictability of the virus and its potential to spread if people don't get vaccinated. "As a nurse and a mother, and an Indigenous woman in this society, it's become even more important and more visualized in my mind how important it is to take care of not only myself and my health, but the health of my family in turn, which could affect the community around me." Her husband Brett Maybee, who works as a media specialist with the Seneca Nation's media and communications center, is tasked with helping to break down the deep-rooted seeds of distrust that still linger within Indigenous communities. Part of that effort is to keep the community informed but also to acknowledge how easy it could be to oversimplify and say that people are wrong to mistrust the vaccine. "There's just all of these things that were under the surface for decades upon decades that we are now forced to confront," he says. "We know a lot of people have passed away and died because of the COVID-19 virus and we haven't stopped thinking about it since it started. But what we can do differently now to help ourselves and our families survive…is get the vaccine."

photograph by Tahila Mintz

As the Chief Operating Officer for the Seneca Nation Health System, Shaela Maybee (no relation to Jade and Brett Maybee) is responsible for being a liaison between the Seneca Nation tribal leadership and the health system. "There was an anxious population ready to get vaccinated," she says. "I think the hardest part at the beginning was having such limited numbers, but it was really nice to work with the Seneca Nation council and executives who had that autonomy of sovereignty to decide who got vaccinated." Prioritizing shots for those with comorbidities and elders was key to the vaccine rollout process. So was tapping fluent Native speakers to continue to provide answers to community members who need to feel reassured and comfortable with getting the vaccine. Shaela Maybee says the reward comes from seeing people actually get the shot. "Lives are getting saved," she says. "People are less likely to have side effects, long-term, from COVID, and hopefully will avoid getting COVID altogether with getting vaccinated." Sheyahshe Littledave, an author and enrolled member of the Eastern Band of Cherokee Indians, contributed to this story.

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||

|

|

||

| Canku Ota is a free Newsletter celebrating Native America, its traditions and accomplishments . We do not provide subscriber or visitor names to anyone. Some articles presented in Canku Ota may contain copyright material. We have received appropriate permissions for republishing any articles. Material appearing here is distributed without profit or monetary gain to those who have expressed an interest. This is in accordance with Title 17 U.S.C. Section 107. | ||

|

Canku Ota is a copyright ©

2000 - 2021 of Vicki Williams Barry and Paul Barry.

|

||

|

|

|

|

The "Canku

Ota - A Newsletter Celebrating Native America" web site and

its design is the

|

||

|

Copyright ©

1999 - 2021 of Paul C. Barry.

|

||

|

All Rights Reserved.

|

||