|

Canku Ota

|

|

|

(Many Paths)

|

||

|

An Online Newsletter

Celebrating Native America

|

||

|

September 2021 - Volume

19 Number 9

|

||

|

|

||

|

Cartographer Focuses

On Storytelling While Mapping Histories Of Places

|

||

|

by HOWNIKAN

|

||

|

Citizen Potawatomi Nation tribal member Margaret Pearce, Ph.D., took one cartography class at University of Massachusetts and spent the next several decades of her life creating and teaching others the art of map-making. "I'd always been an outdoors kind of person and also a kind of a pen-andink person," Pearce said. "And when I learned cartography, or at the time that I was interested in cartography in college, it wasn't really on computers yet. It was still being taught at pen-and-ink level, and that really appealed to me." Toward the end of her bachelor's degree, her next steps were unclear. A mentor and teacher helped Pearce prepare for graduate school applications, and she continued to study. The Burnett family descendant graduated with a doctorate in geography from Clark University in 1998, achieving a tenured professorship at the University of Kansas several years later. Pearce enjoyed teaching map design; however, making them remained her passion. In high school, she considered a future career in writing. That desire never went away, and cartography allowed her a space to combine the art and technicality of recording geography with storytelling. "I thought it would be more about math and measure, which it is. But … as I started to study it, I learned that it was more about language and about composing a narrative about places and whether that's through number or through story or through both through their intertwining. And that just completely changed my life when I learned that," Pearce said. Teaching graduate students map design left little time to practice the discipline on her own – either as a hobby or for a living. After careful consideration, she left her tenured position in 2015 to pursue her passion. "I thought if I could simplify my life because I knew I would have to live very small and cheaply in order to make it, I can do this full time and get further into cartography, which is what I wanted for my life," Pearce said.

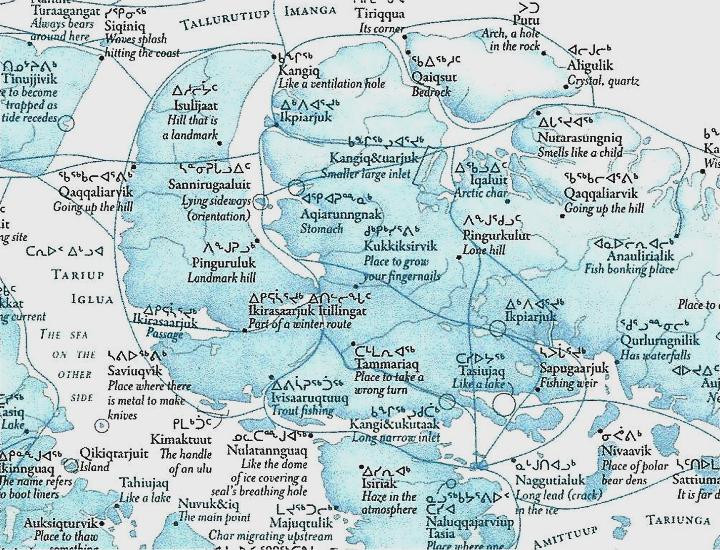

Shape, size and color Clients and individual projects fill her time as an independent cartographer. She designs each map to best serve its purpose at every level. Pearce composes a unique piece using shape, size and color, comparing it to a film director's use of sound, light and framing. A map charting a fur trade clerk's first journey across Canada and the Great Lakes by boat uses all three elements to catch and keep the viewer's attention. She felt the need to construct it after reading the clerk's diaries and feeling dissatisfied with the small, undetailed charts of the more than 2,000-mile journey that came with it. "You had no understanding from looking at the map what at all was happening," Pearce said. "And I thought, 'As a cartographer, I can really bring some of that energy that you get from the diary and bring it into the map so we can feel some of that while we're also learning about where this is all taking place.'" It spans more than 5 feet, forcing the viewer to slow down and pay attention as they move along the trading party's path. Pearce marked sections along the coast to show each day's progress. "As the day gets harder, as they slow their pace, those squares get smaller, and you literally stop moving as you're moving along, reading the map because they are stopped. And I really was enjoying playing with this idea of pace," she said. She also used shades and hues of colors to portray emotion. Green showed quick-moving and happy days, perhaps with good weather, and dark grey marked hard days with sickness or biting cold, at times when death seemed like a distinct possibility. "I was trying to use those techniques of color and the emotion in his words. And the pacing of the day to convey this feeling of, 'What does it mean to look back on a terrifying and also joyful journey? Like what would that feel like? And how can I then express that to the map reader?'" Pearce said. She also included small diary excerpts, and these types of projects make her see the field as a combination of art and science. "As I got deeper and deeper into (my studies), I thought, 'Well, … what it really is, is language because it has this formal structure of expression.' And once we start looking at it that way, then we can expand that language the same way that we expand spoken language or written language," Pearce said. Language, history and today Pearce has worked on many Indigenous projects for tribes and Native nations as well as journalistic publications throughout the years. For example, she designed the printed maps, graphs and infographics for the Landgrab universities project published in 2020 by High Country News. It shows the costs and effects, both monetary and cultural, of the landgrant university system on Native communities across the United States. "I feel like our Indigenous geographies, our stories, get stereotyped sometimes as being only about story. But there's so many important narratives, historical narratives, for us and present narratives for us to tell that need to be told through number," Pearce said. She also enjoys bringing together the past and present through Indigenous languages. One of her most recent projects included creating a map for the University of Maine's Canadian-American Center, Coming Home to Indigenous Place Names in Canada. It marked the anniversary of the Canadian Confederation, and she sought to create a map that celebrated Indigenous sovereignty through language. It shows Inuit and First Nations names for culturally significant places throughout the country, only labeled in those in those peoples' languages. "I basically just started calling and emailing and texting communities in Canada and saying, 'Would you like to contribute place names to this map? And if so, could you please tell me which names you would like to see there?'" Pearce explained. The different languages flow across the map between communities and writing styles, ranging from Roman characters to syllabics. "I didn't try to classify them by language. I didn't try to separate them by time period. I see those as colonizing ways of portraying place names. Instead, I looked to ways to put them in this uninterrupted dialogue," Pearce said. The maps connect the places through ice and winter roads as well as conventional highways, using them as orienting markers. "I saw those roads as really important and … as a way of conveying that these are real places. They're not from the past. They come from the past, but they reside in the present. And they are specifically at these places along the roads that people drive on every day," Pearce said. She believes cartography, in particular, lends itself to the representation of Indigeneity because the land remains at the center of many societies and traditions. "If all of our knowledge is situated and our histories are located at places, and we learn by visiting those places and activating them in our memory … cartography allows us to elevate that important structure and place it at the center," she explained. Pearce hopes the trend of creating maps for Native nations and Indigenous communities continues. However, her interests span far and wide, covering many subjects she feels "desperate to map" in her lifetime. See Land-grab universities at cpn.news/landgrab and Coming Home to Indigenous Place Names in Canada at cpn.news/cominghomemap. Read more about Margaret Pearce's work online at studio1to1.net. |

||

|

|

||

|

|

||

| Canku Ota is a free Newsletter celebrating Native America, its traditions and accomplishments . We do not provide subscriber or visitor names to anyone. Some articles presented in Canku Ota may contain copyright material. We have received appropriate permissions for republishing any articles. Material appearing here is distributed without profit or monetary gain to those who have expressed an interest. This is in accordance with Title 17 U.S.C. Section 107. | ||

|

Canku Ota is a copyright ©

2000 - 2021 of Vicki Williams Barry and Paul Barry.

|

||

|

|

|

|

The "Canku

Ota - A Newsletter Celebrating Native America" web site and

its design is the

|

||

|

Copyright ©

1999 - 2021 of Paul C. Barry.

|

||

|

All Rights Reserved.

|

||