|

Canku Ota

|

|

|

(Many Paths)

|

||

|

An Online Newsletter

Celebrating Native America

|

||

|

September 2021 - Volume

19 Number 9

|

||

|

|

||

|

A Brand-New Museum

In Oklahoma Honors Indigenous People At Every Turn

|

||

|

by Jennifer Billock

- Travel Correspondent Smithsonian Magazine

|

||

|

The team behind

the First Americans Museum in Oklahoma City incorporated the traditions

and spiritual beliefs of 39 tribal nations into its design

At 175,000 square feet, the new First Americans Museum (FAM) in Oklahoma City is the largest single-building tribal cultural center in the country, honoring Oklahoma's 39 tribal nations and housing the National Native American Hall of Fame. The museum opened this month after three decades of planning, and a design process that strove for an architectural masterpiece that would be meaningful to the tribes represented within it. The FAM's tribute to the state's tribal nations begins before you even walk through its doors. In the shape of two partial circles that intersect, the museum grounds function as a huge cosmological clock, tracking the seasons by showing the movement of the sun across the circles and highlighting the equinoxes. The museum buildings make up one circle, and an enormous earthen mound made from 500,000 cubic yards of dirt forms the other. Circle and spiral shapes hold symbolic meaning in First Americans' spirituality, and it was of the utmost importance to include them in the design, explains Anthony Blatt, principal with Hornbeek Blatt Architects, which worked on the museum with design architect Johnson Fain. "There is no end because time is circular in Native cultures. The sun travels around the Earth," says Blatt. John Pepper Henry, a member of the Kaw Nation and the director and CEO of the FAM, adds, "Right angles are not an aesthetic for many of the tribes here in Oklahoma. In our beliefs, if you have a right angle, spirits get trapped in there and it causes an imbalance. So, all of our dwellings are round."

Visitors can walk to the top of the earthen mound to get a sprawling view of Oklahoma City, and on the equinoxes, they can have an extra special experience. On the winter solstice, the sun shines directly through a tunnel cut into the mound, flooding the interior field (the museum's Festival Plaza) with light. On the summer solstice, the sun sits perfectly at the apex of the mound. Getting to the point where all the stakeholders in the museum, funded by the state of Oklahoma, Oklahoma City and the Chickasaw Nation, agreed on a design was a strenuous process, starting back in the late 1990s. "The challenge for the architects was to find symbolism and design that wasn't too specific to one tribe or the other, but to find those common elements to be able to create a design familiar to any tribe that comes here," says Pepper Henry. "But it's not too specific where one tribe feels like we're playing favorites to one over another." To accomplish that, the architects, the design team, landscape architects, Native consultants, a theatrical consultant, and others worked closely with tribal members from each nation to pick the site for the museum and to listen and learn about their different traditions in order to incorporate them into the space.

"What started happening was they started hearing some commonalities," says Shoshana Wasserman, from Thlopthlocco Tribal Town and the deputy director at the FAM. "There is this philosophical approach to connectivity, to the natural world, life-sustaining elements like fire, wind, water, Earth. So, these started emerging. That connectivity to Mother Earth became so powerful, and so that's the direction it went." The entire museum is aligned with the cardinal directions, with the entrance at the east to represent how Indigenous homes always have east-facing entrances to greet the morning sun. A massive arch sculpture by father and son Cherokee art team Bill and Demos Glass borders the entrance, and on the equinoxes, the sun interacts with this arch, perfectly framing it in light. Flanking the FAM's front door are two walls of Mesquabuck stone, named after Potawatomi Indian Chief Mes'kwah-buk, a chief and distinguished warrior from what's now Indiana, who was named after the colors at sunrise and sunset. The name roughly translates to "amber glow," and when the morning sun shines through the arch, it sets the stone aglow.

The two circles of the museum also pay tribute to ancient and modern Native communities. "[The mound is] an homage or nod to our ancestors and the great civilizations that were here before us," Pepper Henry says. "A lot of people don't think of this part of the country as being occupied by humans for thousands of years, but one of the great civilizations in North America was right here in Oklahoma, at the Spiro Mounds. The other circle [the museum footprint] is our modern times." The two circles intersect at a space called the Hall of People, a 110-foot-tall glass dome designed after the grass lodges used by the Native Wichita and Caddo communities before other tribes arrived in the area. Ten columns in the Hall of People represent the ten miles a day Indigenous people were forced to walk during relocation to Oklahoma. In 1830, President Andrew Jackson signed the Indian Removal Act—legislation that promoted white settlement and forced about 125,000 Indigenous people living in Tennessee, Georgia, North Carolina, Alabama and Florida to move to Oklahoma. Walking on a path we now know as the Trail of Tears, thousands died along the way.

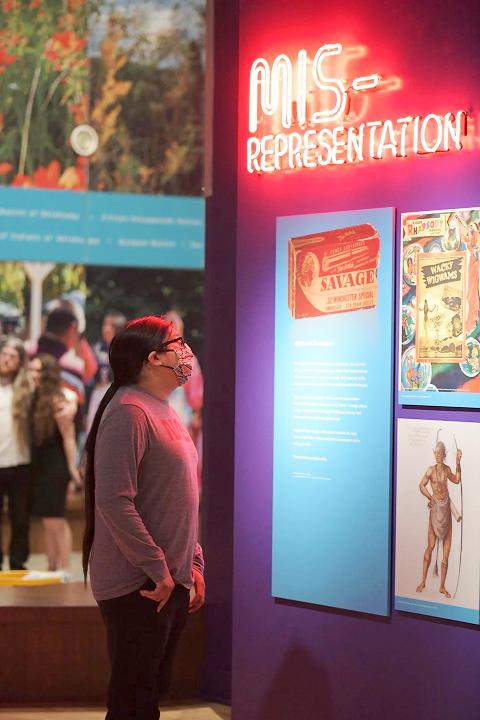

Moving inside, the FAM's exhibit design reflects other important aspects of First Americans' history and spirituality. In the South Gallery, for example, visitors follow parallel timelines, one on each side of the gallery. The side representing the European timeline of Native history is straight and linear. The side representing the Indigenous interpretation of the timeline is circular. "One you march down, the other one you circle through and circle through and come out, and it never stops," Blatt says, explaining that European history is perceived as very linear, while Indigenous concept of time is more circular and rounds onto itself. Overall, the FAM has three main exhibit galleries, two theaters and two restaurants focusing on Native food. The collection explores the authentic history of First Americans, their contributions to society and the cultural diversity among the 39 tribes in Oklahoma. Some of the highlights of the museum include artwork throughout the exhibits, like a massive piece of traditional pottery designed by Caddo and Potawatomi artist Jeri Redcorn and made into a theater; an explanation of the symbolism of stickball (the precursor to modern lacrosse) and game artifacts; and first-person stories told inside the "OKLA HOMMA" exhibit. The National Native American Hall of Fame will move to the museum site in the future from its current location in Montana.

The FAM has a partnership with Smithsonian's National Museum of the American Indian. The two institutions signed an agreement in 2007 for the Smithsonian to loan the FAM 135 items, from clothing and textiles to tools and toys, for ten years. The artifacts, on display in an 8,000-square-foot gallery called "WINIKO: Life of an Object," were all collected in Oklahoma and have connections to each of the 39 tribes that lived there in the 1800s. "One of the priorities of our loans program is to place objects under our stewardship closer to their communities of origin," says Rachel Shabica, supervisory registrar at the National Museum of the American Indian. "This loan provided us with the opportunity to collaborate with a Native-run institution to highlight Native collections in their place of origin. The partnership between NMAI and FAM will enhance the general awareness and understanding of the history of the 39 tribes and their relationship to Oklahoma today."

"WINIKO" is divided into three separate sections. The first covers cultural materials, such as regalia made with lynx fur for a Comanche baby and daily-use woven bags, and how they were created. The second section highlights the disconnect and cultural loss that happens to artifacts when they're removed from their tribe of origin. For example, one display shows each item on a flipping panel. One side shows how the museum world looks at the object, in terms of basic (and often incorrect) information and how much the item is valued at monetarily. But when visitors flip the panel, they learn about how the item was used and the personal value it holds in Native cultures. The third part of "WINIKO" is about the "cultural continuum," as Wasserman calls it. "This cultural continuum is basically stating in the broadest sense that these cultural materials that were collected at the turn of the century are as important and as relevant today as they always have been," she says. "In fact, we continue to make these kinds of items in a contemporary context, and we continue to use them." One section of the cultural continuum gallery focuses on five artifacts, including a hat worn by a young Modoc girl on the Trail of Tears, that the FAM and Smithsonian reunited with the original owners' descendants. As curators were putting together the items for the gallery, they began to recognize names from the local Indigenous communities. After digging deeper, they learned the items belonged to these community members' descendants. "We began to talk to these communities and understand the stories associated with [the items]," Wasserman says. "[They] all had a beautiful homecoming with either the descendants or the tribe of origin, and these were filmed and documented. The Smithsonian allowed the community members, in a private space, to lay their hands, their DNA on the cultural materials of their ancestors who created it and whose DNA was on it. It was so powerful and so spiritual and so emotional." The physical objects are on display, and videos of the reunions play on a screen around the corner from them.

One poignant moment helped Wasserman, at least, conclude that the detailed design process was a success. When a tribal elder was at FAM for a museum preview, she told one of the employees that the museum felt like home. "When I heard that comment—it was just really, really powerful," says Wasserman. "From the moment you arrive, you're making this ceremonial east-west entrance. The average person coming in is not paying attention to that, but Native people, as they're coming in, there's a knowingness. There's a connectivity that is immediate, it's visceral." Most of all, though, Wasserman hopes the museum can help younger Indigenous communities feel like they have a place that is a reflection of them and their culture. "When my niece and nephew go sit in a classroom, they're not present in America's history," she says. "They're not present in Oklahoma's history, and that's demeaning. It's degrading, and it's minimalizing, and it means 'I mean nothing,' and that has had spiritual impacts on our youth. The trauma that perpetuates and lives on in our communities, it's a very real thing. So, I hope this can be just a really beautiful place of healing."

Jennifer Billock Jennifer Billock is an award-winning writer, bestselling author, and editor. She is currently dreaming of an around-the-world trip with her Boston terrier. Check out her website at jenniferbillock.com. |

||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

||

|

|

||

| Canku Ota is a free Newsletter celebrating Native America, its traditions and accomplishments . We do not provide subscriber or visitor names to anyone. Some articles presented in Canku Ota may contain copyright material. We have received appropriate permissions for republishing any articles. Material appearing here is distributed without profit or monetary gain to those who have expressed an interest. This is in accordance with Title 17 U.S.C. Section 107. | ||

|

Canku Ota is a copyright ©

2000 - 2021 of Vicki Williams Barry and Paul Barry.

|

||

|

|

|

|

The "Canku

Ota - A Newsletter Celebrating Native America" web site and

its design is the

|

||

|

Copyright ©

1999 - 2021 of Paul C. Barry.

|

||

|

All Rights Reserved.

|

||