|

Canku Ota

|

|

|

(Many Paths)

|

||

|

An Online Newsletter

Celebrating Native America

|

||

|

September 2021 - Volume

19 Number 9

|

||

|

|

||

|

Grand Ronde Tribe

Reclaims Willamette Falls, As Work Begins To Tear Down Oregon City

Mill

|

||

|

by Jamie Hale | The

Oregonian/OregonLive

|

||

After a private blessing and a prayer, the Confederated Tribes of Grand Ronde invited gathered media to watch as an excavator tore into a wall of the old, abandoned paper mill that the tribe says has stood on its ancestral grounds for too long. The tribe held a symbolic demolition event at the old Blue Heron Paper Mill at Willamette Falls on Tuesday, representing a small step toward removing the industrial site and returning it to Indigenous hands. Chris Mercier, vice chair of the Grand Ronde Tribal Council, said the tribe has been trying to reclaim as much of its traditional homelands as possible. The acquisition of the land at Willamette Falls represents the biggest step in that direction, he said. "This site here is of deep historical and cultural significance," Mercier said at Tuesday's event. "The fact that we've actually purchased it and own it now is kind of a dream come true for many of us and many of our tribal members, because our roots run deep here."

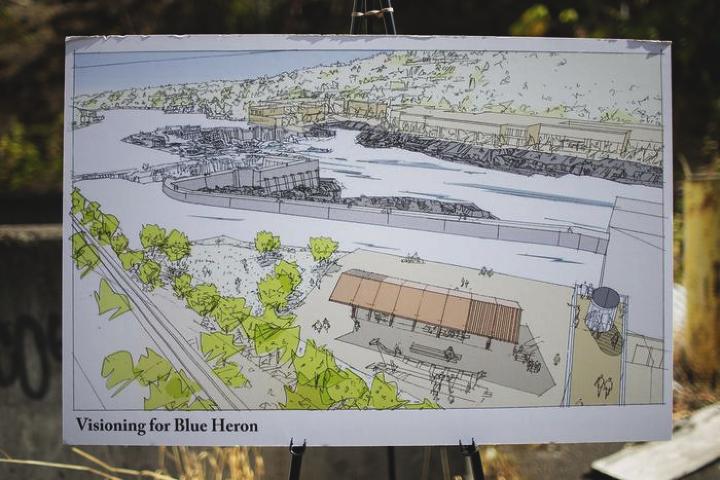

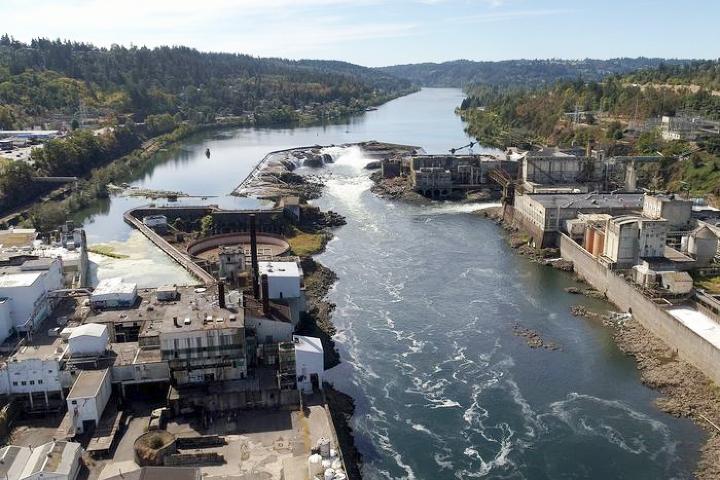

The land around Willamette Falls was once home to the Clowewalla and Kosh-huk-shix villages of the Clackamas people, who ceded the land to the U.S. government under the Willamette Valley Treaty of 1855 before being forcibly removed and relocated, according to the Confederated Tribes of Grand Ronde. For generations, the falls were also frequented by residents of other Indigenous villages around the area, including the Chinookan peoples of the lower Columbia River, who today are represented by several different tribal bodies. The Grand Ronde call Willamette Falls "tumwata," which is the Chinook jargon word for waterfall, and refer to the river as "walamt." Every year, members of Oregon tribes visit the waterfall to harvest lamprey – a prehistoric eel-like creature that has been caught there for thousands of years – along with salmon and other fish. Located on the Willamette River at Oregon City, Willamette Falls has long been one of Oregon's best, least-accessible natural wonders, with public access blocked off by the paper mill that shut down in 2011. In 2019, the Confederated Tribes of Grand Ronde purchased the land, valued at $2.9 million, and earlier this year the tribe laid out an ambitious vision that would transform the old mill site into a community center where visitors could walk along the river, dine at a restaurant, stay the night or attend an event. The plans also include space for tribal members to hold ceremonies near the waterfall. Stacia Hernandez, chief of staff to the Grande Ronde Tribal Council, said that vision will likely take years to complete. With any luck, the property will be cleaned up and safe for the public within two to three years, she said, though construction on other buildings is expected to take longer. When it's finished, however, the Willamette Falls site promises to be a place that is special for both tribal members and the general public alike. "We want it to be a very welcoming and inviting place and we want people to have a real experience when they come here," Hernandez said. "We don't want it to be a show-up, grab-a-cup-of-coffee-and-leave place. We want people to be able to experience it and feel the falls."

In total, the site has space for up to 300,000 square feet of new buildings, the tribe said, and would be a natural extension of downtown Oregon City. Current plans call for Main Street to simply be extended into the newly developed area. Plans are similar to those previously drawn up by the Willamette Falls Legacy Project, a collaborative partnership between Oregon City, Clackamas County, Metro and the state of Oregon. The partnership officially organized in 2014 to find a way to provide public access to Willamette Falls and had previously secured an easement on the property to create a riverwalk. "We're excited about the progress at the Blue Heron site," Carrie Belding, spokesperson for the Willamette Falls Legacy Project, said. "We support the Confederated Tribes of Grand Ronde's vision and look forward to continuing working together." Now, the Confederated Tribes of Grand Ronde, the Willamette Falls Legacy Project and the Willamette Falls Trust (a nonprofit tasked with raising money for the planned riverwalk) are all working together on the project. The first phase of the riverwalk project is estimated to cost $65 million, the trust said, and so far $28 million has been raised in public and private funds. An additional $20 million in public funding is earmarked for the overall project, as part of the Metro Parks and Nature Bond passed by voters in 2019. In August, that collaboration expanded to include four additional tribal governments with ancestral ties to Willamette Falls: the Confederated Tribes of Siletz Indians, Confederated Tribes of the Umatilla Indian Reservation, Confederated Tribes of Warm Springs, and the Confederated Tribes and Bands of the Yakama Nation. Gerard Rodriguez, associate director for the Willamette Falls Trust, said the recent influx of Indigenous voices has created a new "expanded table" when it comes to who will determine the future of Willamette Falls, and, thankfully, all parties involved seem to agree on what should be done. "There's general support of the vision that the Grand Ronde put out in the spring of 2021," Rodriguez said, as well as plans originally proposed by the Willamette Falls Legacy Project in 2017. "Aligning both of those plans is a necessary part of moving forward with the project and creating a shared vision." Both plans call for public access, as well as extensive environmental rehabilitation of the area by removing industrial structures and restoring habitat for salmon, lamprey and other aquatic species. The event Tuesday was a groundbreaking of sorts that represents one of the clearest steps forward at Willamette Falls in nearly a decade of planning. "We're excited to share this place with people," Hernandez said. "For us, it's an opportunity not only to come home to this place and reclaim this place, but to make it better and leave it better for future generations." In addition to its cultural significance, Willamette Falls ranks among the most impressive waterfalls in Oregon thanks to an average volume of about 32,000 cubic feet per second during the rainy season – more than 200 times the flow of Multnomah Falls. Visitors hoping to see the falls will find no public access points along the Willamette River now, though the waterfall is visible from a viewpoint on the side of Oregon 99E, and from the McLoughlin Promenade in Oregon City. For years, the best way for the general public to see Willamette Falls up close has been on one of several boat tours that run up the Willamette River. With the Confederated Tribes of Grand Ronde's purchase and redevelopment of the old Blue Heron site, there will soon be not only good public access, but also a chance for Indigenous communities to once again have a strong, year-round presence at Willamette Falls, the tribe said. "It's a chance for us to tell our story," Mercier said at Tuesday's event. "What we do here will reflect the value and the mission of this tribe." |

|

|

||

|

|

||

| Canku Ota is a free Newsletter celebrating Native America, its traditions and accomplishments . We do not provide subscriber or visitor names to anyone. Some articles presented in Canku Ota may contain copyright material. We have received appropriate permissions for republishing any articles. Material appearing here is distributed without profit or monetary gain to those who have expressed an interest. This is in accordance with Title 17 U.S.C. Section 107. | ||

|

Canku Ota is a copyright ©

2000 - 2021 of Vicki Williams Barry and Paul Barry.

|

||

|

|

|

|

The "Canku

Ota - A Newsletter Celebrating Native America" web site and

its design is the

|

||

|

Copyright ©

1999 - 2021 of Paul C. Barry.

|

||

|

All Rights Reserved.

|

||