|

Canku Ota

|

|

|

(Many Paths)

|

||

|

An Online Newsletter

Celebrating Native America

|

||

|

September 2021 - Volume

19 Number 9

|

||

|

|

||

|

How Native Students

Fought Back Against Abuse And Assimilation At US Boarding Schools

|

||

|

by The Conversation

|

||

As Indigenous community members and archaeologists continue to discover unmarked graves of Indigenous children at the sites of Canadian residential schools, the United States is reckoning with its own history of off-reservation boarding schools. In July 2021, nine Sicangu Lakota students who died at the Carlisle Indian Industrial School in Pennsylvania were disinterred and returned to their homelands at Whetstone Bay in South Dakota.

One of these young people was Ernest Knocks Off. Ernest, who came from the Sicangu Oyate or Burnt Thigh Nation, was among the first group of students to arrive at Carlisle, in 1879. He entered school at age 18 and attempted to run away soon after arriving. He ultimately went on a hunger strike and died of complications of diphtheria on Dec. 14, 1880. My new book “Writing Their Bodies: Restoring Rhetorical Relations at the Carlisle Indian School” explores how Indigenous children resisted English-only education at Carlisle, which became the prototype for both Indian schools across the U.S. and residential schools in Canada. While digging into archives of Carlisle students’ writing, I found that young people like Ernest were not passive victims of U.S. colonization. Instead, they fought – in Ernest’s case, to his death – to retain their languages and cultures as the assimilationist experiment in education unfolded. ‘Unspoken traumas’ U.S. Army Gen. Richard Henry Pratt opened the government-funded Carlisle Indian Industrial School in 1879. Following his model, more than 350 government-funded and church-run boarding schools later opened across the U.S. The National Native American Boarding School Healing Coalition estimates that hundreds of thousands of young Native people attended these schools in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. The first students were recruited by Pratt and sent by their nations in hopes that they could learn English to continue fighting against treaty violations by U.S. settlers. In 1891, attendance became compulsory under federal law. Boarding schools sought to assimilate Indigenous children into Euro-Western culture by separating them from their communities. The schools forced them to learn English and practice Christianity and trained them to work in a capitalist economy – often as servants and laborers on farms and in the households of white people. Students experienced physical abuse, sexual violence and hunger, and hundreds died of diseases like tuberculosis that spread rampantly in institutional settings. Canada’s national Truth and Reconciliation Commission identified 3,201 children who died in Canadian residential schools. No such estimate exists in the U.S., where a formal reckoning has yet to occur. However, U.S. Interior Secretary Deb Haaland, a member of the Laguna Pueblo Nation, has pledged to “address the intergenerational impact of Indian boarding schools to shed light on the unspoken traumas of the past.” Even as Indigenous students faced teachers and a government trying to replace their cultures, languages and identities, they resisted the assimilationist education. Their strategies were at times blatant, but often covert.

Running away Running away was a way for students to communicate their rejection of assimilationist education and to fight their separation from their homeland and community. Runaways sometimes succeeded and got back home. But I believe that even when they were forcibly returned to school, running away represented courage and reminded the other students to keep fighting. Plains Sign Talk Plains Sign Talk is a sign language that serves as a lingua franca for trade and diplomacy among the Pawnee, Shoshone, Cheyenne, Arapaho, Crow and Siouan peoples in the Southern Plains. It became a powerful tool at Carlisle, where teachers demanded that students give up their languages for another shared tongue – English. Plains Sign Talk was a way for students to communicate with one another and across tribes that was unintelligible to their teachers. Carlisle teachers underestimated the importance of Plains Sign Talk, viewing it as a primitive form of communication that students would leave behind as they learned English. When Pratt and his colleagues witnessed students using it, they created a new curriculum based on techniques used to teach deaf students. They did not realize that students were using the sign language to circumvent the English-only policy.

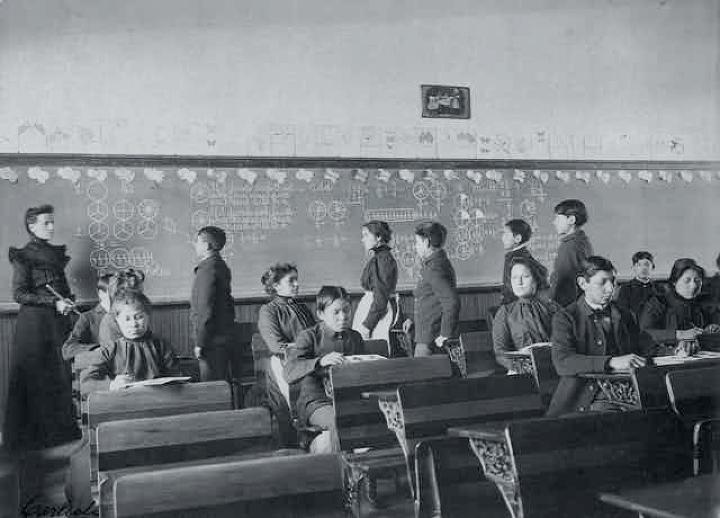

Pictographic writing Students also drew on Plains pictography to tell their stories. Plains tribes originally painted pictographs – elements of a graphic writing system – on buffalo hides to document victories in battle and record “winter counts,” or annual historical records. After increased contact with settlers, many tribes began to document pictographic histories in ledger books. These texts served as communal histories that would prompt oral retellings of battles and other significant events. Students at Carlisle regularly used pictographs on slates or chalkboards. On June 25, 1880, for example, a Cheyenne student who was renamed Rutherford B. Hayes at school drew a pictograph of a horse and rider on his slate. He labeled the image John Williams – the Carlisle name of an Arapaho boy who was his classmate and friend. I argue that these pictographic records show how some students understood their time at school in the context of their developing warrior identities, underscoring their desire to act bravely and return home to recount their stories for their nations’ collective memory. Speaking Lakota When students spoke their languages, they faced harsh penalties. This included corporal punishment, incarceration in the campus barracks and public shaming in the school newspaper. Pratt and his supervisors at the Bureau of Indian Affairs hoped that they could break up tribes by disrupting the transmission of language and culture from one generation to the next. By destroying tribal identities, they hoped to take land in communally held reservations and guaranteed by treaties. For U.S. settlers to gain access, the land would have to shift to a private property system. Boarding schools thus became part of the federal Indian policy later codified as the 1887 Dawes Act. Although students were supposed to speak only English, they began to learn one another’s languages as well. Lakota, or Sioux, became particularly popular, as it was a majority language in the school’s early years when many students came from the Rosebud and Pine Ridge reservations. In 1881, Pratt was troubled that students were still speaking their languages two years into their term. When student Stephen K. White Bear was found “talking Indian,” he received a common punishment, which was writing a composition about his discretion. In his essay “Speak Only English” Stephen revealed that “every boy and every girl would like to know how to talk Sioux very much. They do not learn the English language they seem to want to know how to talk Sioux.” Seeds of pan-Indian resistance As students met peers across nations as geographically far-flung as the Inuit and the Kiowa, they sowed seeds for the pan-Indian resistance movements of the 20th century. From the founding of the Society of American Indians in 1911 through the American Indian Movement of the 1960s and ‘70s, Native activists unified for advocacy and cultural revitalization. Scholars argue that these movements can trace their roots to intertribal communities of solidarity that were built in the boarding schools. The outcry against boarding schools that we see today across Canada and the U.S. reflects not only a shared experience of trauma, but a longstanding solidarity among Indigenous peoples working together to maintain land, language, culture and identity in the face of oppression at the hands of Euro-Americans. |

||||||||

|

|

|

|

||

|

|

||

| Canku Ota is a free Newsletter celebrating Native America, its traditions and accomplishments . We do not provide subscriber or visitor names to anyone. Some articles presented in Canku Ota may contain copyright material. We have received appropriate permissions for republishing any articles. Material appearing here is distributed without profit or monetary gain to those who have expressed an interest. This is in accordance with Title 17 U.S.C. Section 107. | ||

|

Canku Ota is a copyright ©

2000 - 2021 of Vicki Williams Barry and Paul Barry.

|

||

|

|

|

|

The "Canku

Ota - A Newsletter Celebrating Native America" web site and

its design is the

|

||

|

Copyright ©

1999 - 2021 of Paul C. Barry.

|

||

|

All Rights Reserved.

|

||